Topic outline

-

The teaching philosophy The role of the lecturer Teamwork is important Courses are for all students How hard are these courses? Will these courses make you an expert? A teaching philosophy of "engagement" - based on continuous improvement

The teaching philosophy is to engage students in entrepreneurship courses to enhance the learning experience by using a creative combination of innovative teaching methods that are continuously evaluated and improved.

This philosophy has evolved over many years as a result of continuous innovation in teaching methods, systematic student evaluation of these methods, and extensive reference to the literature on entrepreneurship education and student engagement.

The aim is to help all students to develop both professionally and personally, and in particular to encourage self-confidence, and to provide the knowledge and tools for UniSA graduates to be more enterprising individuals at the personal, community, and industry levels.

This philosophy supports the School of Business areas of priority for teaching and learning

School of Business priority: How the School of Business priorities are addressed in these courses Student engagement: This website describes a range of methods that have been selected and refined to encourage student engagement. These include Team-Based Learning, a single project idea for a class, the poster plan, the plan presentation and review session. Many other activities are listed that contribute to engagement.

Transition to practice: Entrepreneurship courses are by their nature integrative and practice-oriented. students are challenged by real projects that require engagement with the community by carrying out face-to-face interviews. In addition, courses emphasise the ways in which theoretical models and constructs can be related to practical application.

Feedback to students: The Team-Based Learning approach is based on providing prompt feedback on learning outcomes. The single project idea and the project presentation and review sessions provide immediate feedback on the major assessments.

Development of collaborative working skills: Student evaluation shows that the Team-Based Learning approach is a very effective means for developing both student engagement and collaborative working skills. This approach is supported by giving students the opportunity to obtain anonymous and positive feedback from their team members on their contribution to teamwork.

This philosophy is underpinned by systematic student evaluation for continuous improvement

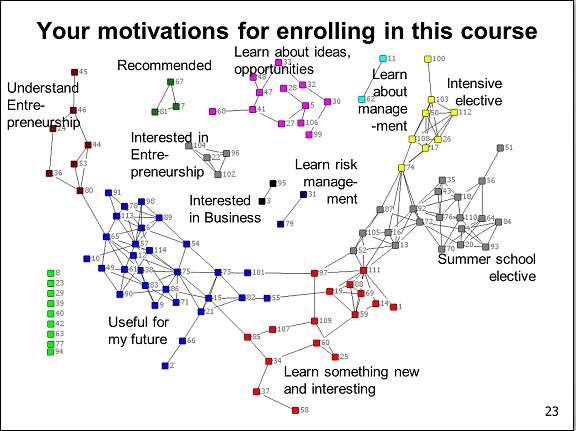

"Minute evaluations" have been used in these courses for more than 10 years as a focused method for obtaining anonymous student evaluations, as well as suggestions for improvement, of each of the teaching methods and activities used in these courses. This approach is also supported by systematic research into student perceptions and behaviours. For example, student learning motivations are identified for each course delivery, and this information is used to advise the teaching approach for the particular class.

This systematic evaluation of individual teaching activities, leading to continuous innovation in entrepreneurship courses, has been recognised by a national teaching award - an ALTC Citation.

Why is there systematic evaluation of these courses?

The overall aim is to find approaches that enhance student engagement in these courses, and this is done in two ways.

Firstly, staff draw on the literature in entrepreneurship and enterprise education to identify "best practice" in teaching methods and approaches. For example, the course coordinator has benchmarked this course against international studies of entrepreneurship courses (OECD, 2008, 'Entrepreneurship and Higher Education', OECD, Paris, and Katz, J, 2008, 'Fully Mature but Not Fully Legitimate: A Different Perspective on the State of Entrepreneurship Education', Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 550-566)

Secondly, staff experiment with new approaches and activities. Student evaluations provide ideas for improvements.

This is why staff carry out simple but effective evaluations of all new activities and approaches that they introduce into the entrepreneurship courses. In particular, students are asked to comment on activities and suggest improvements.

In summary, staff apply continuous improvement to all courses, with reference to the literature on entrepreneurship education and guided by student evaluation of this course.

The course coordinator has gained several awards (UniSA and national) for excellence in teaching, primarily for innovation in teaching in the entrepreneurship courses.

What is the lecturer's role in these courses?

The people who deliver entrepreneurship courses are actively engaged in the three key areas that characterise a university: teaching, industry collaboration, and research.

Research into entrepreneurship and innovation underpins teaching activities. in particular, this means that we:

- Keep up-to-date with current knowledge in our field by reading academic papers, industry reports, and business news. This ensures that we include in our courses leading-edge and relevant material

- Critically assess the existing and emerging knowledge in our field and present it in a concise and accessible manner in our teaching materials

- Present the content in a way that relates clearly to industry and community contexts

- Design the course content, teaching materials and teaching methods to help you to be successful in this course

- Allow you to test your learning and understanding through the exercises that we use in our courses and through the course assessments (project reports and exams)

- Provide critical feedback/comments during classroom discussions and on project reports to help you to develop your understanding of the field. Because discourse is a very important aspect of learning, we encourage classroom discussion, but our role is to be critical and challenge students to think more critically, precisely so that students will learn. This is important, because a key aspect of our work is to critically assess everything we read or hear and test whether it matches the theories, models, and practice in this field. At the same time, students must appreciate that our job is to be analytical and to critique in an objective manner what we read or hear; we are not criticising or making any reflections on the person who is writing or saying something that we critique.

- Apply continuous improvement to all aspects of the course. This is why we review our courses after each delivery to ensure that the content is as up-to-date as possible, and why we carry out frequent evaluation and feedback exercises to help us to improve our teaching methods. In addition, we experiment with different teaching methods, by taking ideas from other disciplines and universities, and evaluating them to see if they are effective in our situation.

Dr Peter Balan OAM

Dr Balan OAM has developed most of UniSA's entrepreneurship courses, and has gained UniSA and national awards for his contributions to teaching and to community engagement.

In particular, he has active research programs in innovation and entrepreneurship, and presents papers at leading entrepreneurship and business research conferences. He has developed a research stream in entrepreneurship education, and is collaborating with academics around the world on a number of research projects.He has also developed expertise in Team-Based Learning, and has completed the two-year process to become an accredited trainer in this teaching method, and is mentoring lecturers in other countries.

In 2016 he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) "for service to teritary education, and to the community of South Australia".

Details are on his UniSA homepage.

Teamwork is an important and relevant feature of these courses

Entrepreneurship is frequently described as an individual activity, and a great deal of media attention is focused on individual entrepreneurs.

The reality is that a new venture needs a team to get it up and running. A great deal of research has been carried out into the desired characteristics of new venture teams, and it is well known that venture financiers are more concerned with the quality of the entrepreneurial team than the possible quality of the business idea when considering whether or not to finance a new venture.

In addition, research shows that only one or two students in each of these classes is thinking of starting a new venture. For these reasons, these courses focus on encouraging all students to consider being part of an entrepreneurial team sometime in their careers. A teaching approach based on teamwork is therefore important for giving students the experience of what it might be like to work in an entrepreneurial team.

A second reason for the focus on teamwork is that there is plenty of research to show that most people learn more quickly and more effectively when working in a team. This is why Team-Based Learning is the teaching method used in these courses. In addition, this method is shown to be a more effective way to develop and support productive teamwork than other teaching methods.

These courses are for students from all fields of study

Drawing on student feedback, course content, course delivery and course assessment have been developed so that all students should be able to handle these courses with a reasonable input in terms of hours, thought and application.

For example, in most universities, the foundation course usually requires students to develop a full business plan. In Entrepreneurial Enterprises, however, your team produces a feasibility plan or business case that is much more straightforward to prepare, but still addresses the key aspects of technical, market, and financial feasibility.

In addition, courses are supported with clear learning materials, and detailed templates for producing team reports.

As a result students are drawn from all parts of the University. For example in 2013 the Entrepreneurial Enterprise courses were taken by students from 39 different study programs, and from all UniSA campuses (including Whyalla). These included business, arts, journalism, health sciences, engineering, sports management and information technology students. In addition, these courses regularly include students from other universities (cross-institutional enrolments).

"I am from a non-business background, but found this very interesting and a real eye opener" (Entrepreneurial Commercialisation), "I have come out of my comfort zone to do a management/marketing course, having not previously enjoyed related subjects, and I'm pleased that I have" (Entrepreneurial Enterprises ), "I am an engineering student, and I normally sleep in my lectures, but in this course I just never slept" (Entrepreneurial Enterprises)

Working with students from a wide range of disciplines means that you benefit by learning from others, and seeing that they have a different point of view.

How much work do these courses involve?

Entrepreneurship courses include lecture/seminar sessions, workshops, report presentation and feedback sessions (and some undergraduate courses have written exams).

Whether these courses are offered in semester or intensive mode, they are all equivalent. That is, like any UniSA 4.5 point course, these courses require about 120 hours of your focused learning time to attend lectures/seminars and workshops, to prepare for assignments (and an exam), and to work outside these sessions to collect market information and to prepare a major report. Anything less that this level of input and concentrated effort means that you are short-changing yourself .

In practice, this means that you need to allocate 120 hours of real thought and effort over the duration of the course. If the course runs over 4 weeks, then this is equivalent to 30 hours each week - which is almost a full-time job.

In turn, this means that it is not realistic to expect to hold down a full-time or even a part-time job while taking one of these courses. You need to set your priorities to focus your time, thought and effort on your course and put other activities (work, travel) to one side during the 4 weeks or so that the course runs. Some part-time students take leave from their work so that they can concentrate on the course and do a good job.

Sorting out your priorities to focus on your studies is most important. In an undergraduate course you will need to allocate time to work with your team to carry out the major project. You will need to make teamwork a priority to be fair to your team members. In a postgraduate course you will need to make time to carry out the assignments and the major project by yourself to end up with a good result.

In summary, these are not "short" or "easy" courses. They take at least the same focus and commitment as any other semester-long course. However, the courses have been designed to be completed in the 120 hours and hundreds of students have completed them successfully over the years.

Will these courses make me an expert?

What do you need to become an expert in entrepreneurship?

It is useful to look at the extensive literature on "expertise". A huge amount of research has been carried out over more than 100 years to try to identify what is "talent", and in particular to find out if talent is "God-given", or whether there is some other dimension to "talent".

This research is summarised in Ericsson, K.A, 2007 'The Making of an Expert', Harvard Business Review, Vol 85, No 7/8, Jul/Aug 2007, pp 114-121). A more detailed overview of the research is in Ericsson, KA & Chamess, N 1994, 'Expert Performance: Its Structure and Acquisition', American Psychologist, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 725-747.

In summary, Ericsson identifies four requirements for a person to become an "expert", that is, a person who can consistently deliver above-average performance in their field (whether in physical activities such as sports, or intellectual pursuits such as knowledge acquisition or in skills, such as music). These four requirements are:

- personal motivation to excel

- parental and family support and encouragement

- the right teachers (and moving on to higher-level teachers as you progress)

- 10,000 hours of focused learning (for example, this means 2 to 3 hours of focused music practice each day). In practice, this means about 10 years of effort. Note that this is not the same as "experience" (which may be 10 times one year's experience).

It is useful to put these requirements into the context of a typical university course. The University expects a student taking any 4.5 unit course (like these entrepreneurship courses) to apply 120 hours of concentrated learning to that course. These hours include your time attending lectures/seminars/workshops, studying for tests and exams, working with a team to prepare a major report, and so on.

You can compare this with what is frequently reckoned to be 700 to 800 hours you need to reach a level of conversational French or German, and 2,100 hours to reach a level of conversational Chinese or Japanese.

In other words, if you really apply yourself to one of our courses, you will be 1% on the way to becoming an expert in the field of entrepreneurship.