Topic outline

-

Contents:

- Preparing for a retreat

- During the retreat

- Running a virtual writing retreat

- Writing activities

- Free writing

- Free writing research question prompts

- Pomodoro technique

- Revision strategies

- Handout/discussion points: Seven tips to inspire great writing for creative (and other) writers

- Example retreat program

- Reference

Writing retreats provide researchers with a collective, supportive and dedicated writing space within which to progress their writing. Most of the time during a retreat is used for quiet writing, but writers also benefit from sharing their writing experiences and goals, and shorter structured activities can be included within retreat time. This resource provides information about running a writing retreat, including suggestions for activities to facilitate writing and revision processes during retreats.

Preparing for a retreat

Steps in preparing for a retreat:

- determine a location, it should be quiet and uninterrupted;

- book venue and recruit participants (university computer pools are useful venues if you can't go off campus);

- organise any catering you wish to offer;

- ask participants to prepare for the retreat by setting their retreat writing goal, doing necessary pre-reading, organising any material they may need, etc;

- let participants know what they will need to bring (eg laptops, USB sticks, personal items, swimming or hiking gear [if residential], as relevant);

- make a program and circulate to participants, or have it ready for the day (see example retreat program below);

- set blocks of uninterrupted writing time, from 1.5 hours up to 3 hours, within the program;

- consider whether you’d like to set some writing activities within the program to facilitate genre acquisition, writing or feedback (structured interactive training is best offered in the afternoon or after lunch when many participants begin to tire);

- prepare any teaching materials you will need for the day.

During the retreat

At the retreat:

- If you go away and the retreat is residential, arrive the night before the first day of writing to allow writing first thing in the morning.

- If this is not possible, reduce settling-in time to a minimum and get straight into writing in the morning.

- On the first morning, ask participants to share their individual goals for the retreat.

- Remind participants of ground rules for how the retreat will operate (see example ground rules in timetable below).

- No interruptions during writing time.

- Consider having some stretching or other movement exercises ready and get participants to do them together in the middle of long blocks of writing time.

Common retreat ground rules:

- No email.

- Turn phones to silent.

- If you need to talk, go outside.

- No surfing the net.

- No searching for references (checking references to write about them is ok).

- Network and share in the breaks.

Can you run a virtual writing retreat?

Absolutely! It may be even more important to provide a collective space for people to come together to write during times of social isolation. Simply follow the principles for face to face writing retreats. The main difference is that people are writing in their own physical space, but they are virtually connected. This can convey the same sense of community, and writers can come together to discuss their writing and the writing process enjoying the same benefits as writers sharing a physical location. Some tips for running a writing retreat on zoom or teams:

- Set a time and virtual space for everyone to log on, circulate the schedule, and otherwise prepare writers for the event.

- Following preliminaries, everyone mutes their microphone and writes without interruption.

- Leaving the video on can help to create a sense of others' presence.

- You can use the chat function to share writing goals for the day, and to review these at a later time in the retreat.

- Break out rooms can be used between set writing times.

- And you can schedule times for discussion within the whole group in the same way that you would in a writing retreat at a location.

- Although writer's can't physically go for coffee, they can still get to know one another during the discussion times, and then agree to meet virtually outside of retreat time if they choose.

Writing activities

During the retreat you may wish to schedule activities to support the writing process. Brief discussions about the writing process in which participants share their experiences, challenges and strategies are commonly used and can be helpful. It is also common and beneficial to begin and end the day with a brief round in which participants share writing goals for the day and accomplishments. Some other popular writing process support strategies are listed below.

Free writing (Elbow, 1998)

Peter Elbow’s ‘free writing’ technique is designed to create a space within which writers can explore the meanings or ideas they wish to convey without the inhibitions of criticism or judgement. The free writing activity aims to reduce anxiety and negative feelings about writing, and to expand participants’ writing strategies. It can help to produce more natural language and to make writing easier.

The goal of free writing is to produce a 'zero draft', effectively creating new writing while delaying the revision process. To the extent that we all, even experienced academic writers, write with a critic in our head inhibiting the free flow of ideas, Elbow’s methodologies are useful.

The key message to convey within free writing activities is that well-structured writing does not happen in the mind before writing, but emerges from first rough drafts, or ‘garbage’ writing. Writers can be encouraged to free write 'garbage' on a regular basis (say 15 minutes per day) to establish a routine in which one gives oneself permission to think and to write.

Start by setting a time limit, and asking people to write without stopping within that time limit. Make it clear that no one will look at or judge the writing, and also that the quality of the writing will probably not be of a high standard, even if the content is sound, and that this is ok and 'normal'.

Example instructions to facilitate free writing:

- 'It can sometimes be difficult to start writing when the inner critic insists that our writing should be ‘good’, or organised and streamlined, the first time we write'.

- 'In this writing activity, I want you to choose an aspect of your research that you want to write about and to write without stopping'.

- 'Don’t stop writing to correct, just keep writing'.

- 'If you get stuck, write about what you are stuck on'.

- 'Know that when you are stuck it is useful to write about what you are unsure of. This can help you to identify questions you need to get answers to so you can move forward with your writing.'

- 'Focus on what it is you want to say and the meaning you want to convey to the reader. The only rule is to write about your topic without stopping'.

- 'Know that no one will see this writing. It is for your eyes only'.

- 'Try not to over-think it; focus on getting your ideas down in whatever order they come'.

- 'Accept that writing is messy at first, but that you need to have messy writing before you can have good writing'.

Free writing research question prompts

It is not necessary to have question prompts for free writing; it may even be useful to avoid them. However, some writers may find it helpful to have a question in their mind to write to, helping them to 'know where to start'. Some questions are provided below to serve as prompts to writing about some aspect of research writing. The questions are provided as examples and are not all relevant to all methodologies or disciplines. In a free writing exercise, the writer can put one or more, but not too many, question prompts at the top of a blank page and free write their answers below.

Question prompts for writing about the research justification

- Why does my topic matter?

- Why should anyone care about it?

- What real world problem does it pertain to?

- What negative outcome or wrong idea will there be if the problem is not understood better?

- What positive outcome or potentiality emerges if the problem is understood better?

Question prompts for writing about the literature review

- How do researchers (and creative practitioners as relevant) in my field understand the problem or themes my research (or creative practice) pertains to?

- Within my field, what knowledge is well accepted (or themes well explored) in relation to the problem/focus area?

- Within my field, what are the main findings or approaches on the subject area?

- What conceptual assumptions underpin research and practice in the area?

- What are the implications of existing findings or approaches in the field for practice, policy, methodology or theory?

- What do scholars in my field advocate in the way of solutions to the problem?

- Within my field, are there any divergences or key differences in how the problem is understood or approached, in conceptual underpinnings, or in the implications drawn from findings?

- Are there limitations to how the problem is or can be tackled in my field? What are they? Why do they exist?

- What remains unknown, neglected or contested in relation to the problem or topic?

- What is my research question, aim, objective or hypothesis?

Question prompts for writing about methodology and creative practice

- What did I, or will I do, and why in this way?

- In what order did/will I do it?

- Where did the study take place? Why did I choose this site?

- What type of participants are involved in my study? Why these and not others? What were the selection criteria?

- What experiments and experimental order did I use? Why?

- What materials did I use? Why?

- What documents, policies, laws, institutional practices did I analyse? Why did I choose these ones?

- How did I/will I capture and analyse the data produced by the study?

- How will I record my creative practice? How is my creative practice linked to the conceptual themes my work pertains to?

Question prompts for writing about empirical results/evidence

- What does the data tell me that addresses or answers my aims/question? What insights does the data provide in relation to my questions?

- What did I find that was 'interesting', that is, new in my field?

- What was the most important thing that emerged from my data? Why?

- Did I find anything that was surprising in any way? Why was what I found surprising?

- What might explain what I found? What other studies could shed light on why I might have found this? How? Why?

- What was expected, and what was unexpected, in my findings?

Question prompts for writing discussions and conclusions

- If I had to write one overarching answer to my question, what would it be? What was the big message that emerged from my data about my question?

- What ‘take-home’ message do I want my reader to remember about my research?

- Are my findings surprising and new? Why are they different from what others found?

- What existing work agrees with my findings? What disagrees with my findings? Why?

- How can discrepancies between my findings and those of other studies be explained?

- What do my findings suggest should be done now (regarding policy, theory, methodology, practice)? Is this different or the same as what is already happening? How?

- What obstacles or supports are there in relation to the implications of my findings?

- Are there important questions remaining? Did new questions emerge from my study? If so, how should those questions be tackled?

- Is there reason to think that my findings might not explain the entirety of questions raised by my research? How so? How could this be addressed?

- Are there important caveats I want to make regarding how my findings are read? What are they? Could they be addressed in another study? How?

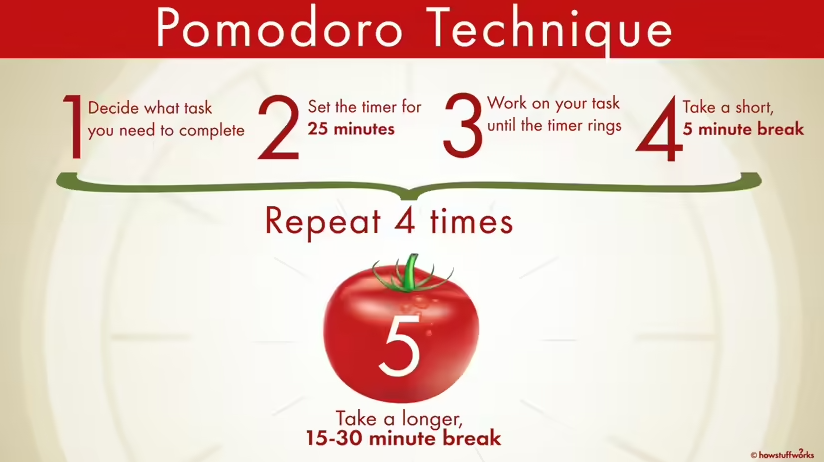

Pomodoro technique

The 'pomodoro technique' is named after the Italian author who used a tomato shaped kitchen clock timer to break up his writing blocks into 25 minute segments with a five minute break in between. Pomodoro means tomato in Italian. The technique is helpful for those of us who are easily distracted, or who tend to work beyond peak productivity when writing. A succinct and light hearted introduction to this simple writing strategy can be found at: The Pomodoro Technique

Writers could be introduced to the technique during a writing retreat by breaking a one-hour (or longer) writing block into 'pomodoros', or 25 minute blocks, with a five minute compulsory break in between during which participants must move away from their desks for rest or chat.

Revision strategies

The revision activities and handout below are designed to make the processes experienced writers use in the revision process explicit. New writers often do not understand the centrality of multiple drafts to the writing process. Writers may move too quickly to editing their work, become overly attached to what they have written and unable to delete or rework it, or they may rely on only a few revision strategies. Academic writing is highly inter-textual, involving close reading and engagement with other authors' texts, as well as with different forms of ‘data’. For novice writers, it can be particularly helpful to elaborate typical approaches to revision within academic writing.

Example instructions to facilitate revising:

- 'Once you have a zero draft, it is time to begin revising'.

- 'Good writing is the product of many, many revisions'.

- 'Revising is not free writing and it is not editing'.

- 'Revising is where most of the writing happens in academic writing'.

- 'Revising is slower than free writing, but it involves elements of free writing and of editing'.

- Consider the different revision strategies below, and continue your revision process.

- Read through the text and add new words, phrases, sentences and paragraphs as needed to carry the flow of ideas.

- Remove repetition and redundancy. If you’re not sure if you might need deleted content later, put it in a separate file away from your current draft.

- Check the meaning of words you are not sure of and use different words if necessary. Use the specialist and generalist dictionaries and thesaurus.

- Move content back and forth to create logical sequence of ideas.

- Write or cut and paste topic sentences towards the beginning of sentences. Check each paragraph to determine its main point. Have one point per paragraph. Check that paragraph breaks pertain to key points.

- Check key points are introduced in the opening and closing paragraphs of sections. Try summarising yourself in the margin of your text in order to do this.

- Check titles of main sections capture the key point of the section.

- Add material from sources you have read as needed.

- Go back to check sources (literature/data etc) to ensure accurate reporting.

- Look for areas of overlap among your report of sources; recraft sentences to include all of them, without misrepresenting any one of them, and place references together in the sentence.

- Check titles of tables and figures to ensure they describe content.

- Ensure commentary before and after tables and figures is explanatory or provides an adequate introduction.

- Provide lead-ins to any direct quotes.

Handout/discussion points to inspire great writing for creative and other writers

In the attached student handout, Monica Behrend summarises a text by Jones (2007) which lists seven strategies that creative writers use to inspire great writing. The strategies suggested are key to much effective research writing, and you are likely to find the handout useful to inform discussions about the writing process in wider disciplines. You may choose to share the handout with HDR candidates to start a discussion about writing, or use/adapt the handout to inform a discussion on writing tailored to your own context and needs.Example retreat timetable

Time

Activity

9.30–10am

Settle in and get your workstation organised.

Ground rules and housekeeping

Introductions–share your name (other important information), and what you plan to work on today/what you want to achieve.10am–12pm

Quiet writing time

12pm–1.30am

Lunch

1.30–2pm

Free writing activity

2pm–3pm

Quiet writing time

3pm–3.30pm

Structured activity or presentation

3.30 – 4.30

Quiet writing time

4.30 – 5pm

Group round: Choose to share from among the prompts below:

‘What I am going to do to strengthen my writing practice is … .‘

Building positive feelings about my writing:

- ‘The best thing about my writing is … ’.

- ‘What I love about writing is … ’.

- ‘I do my best writing when … ’.

- ‘What I love about what I am writing is … ’.

‘My reward for getting some good work done today will be … ’.

‘My writing goal for tomorrow will be … .’ (Write it down or ‘park’ it).

Reference

Elbow, P. 1998. Writing Without Teachers. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford UP.

Jones, D. 2007. The Virginia Woolf Writers’ workshop: Seven lessons to inspire great writing. Bantam Books, New York.