Study design

| Site: | learnonline |

| Course: | Research Methodologies and Statistics |

| Book: | Study design |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 20 February 2026, 2:04 AM |

Table of contents

- Epidemiological Studies Overview

- Experimental Study Designs: Randomised clinical trials

- Experimental Study Designs: Other non-randomised interventional studies

- Observational Study Designs: Introduction

- Observational Study Designs: Cross-sectional study

- Observational Study Designs: Case control study

- Observational Study Designs: Cohort study

- Observational Study Designs: Ecological study

- For More Information on Study Designs

Epidemiological Studies Overview

![]() Epidemiological studies can be descriptive and/or analytical. Descriptive studies are used to describe exposure and disease in a population, and can be used to generate hypotheses, but they are not designed to test hypotheses. Analytical studies are designed to evaluate the association between an exposure and a disease or other health outcome, and therefore are designed to test hypotheses. This module will focus on analytical epidemiological studies.

Epidemiological studies can be descriptive and/or analytical. Descriptive studies are used to describe exposure and disease in a population, and can be used to generate hypotheses, but they are not designed to test hypotheses. Analytical studies are designed to evaluate the association between an exposure and a disease or other health outcome, and therefore are designed to test hypotheses. This module will focus on analytical epidemiological studies.

Epidemiological studies can also be prospective or retrospective. A prospective study is one where the study starts before the exposure and outcome are ascertained. A retrospective study is one where the study starts after the exposure (and probably outcome) has been ascertained.

Other terminology important for epidemiological studies design module:

- Exposure: the risk factor (agent, experience, procedure, etc) that is suspected to have caused the disease. In statistical terms, this is your independent variable.

- Outcome: the disease, endpoint that you are measuring. In statistical terms, this is your dependent variable.

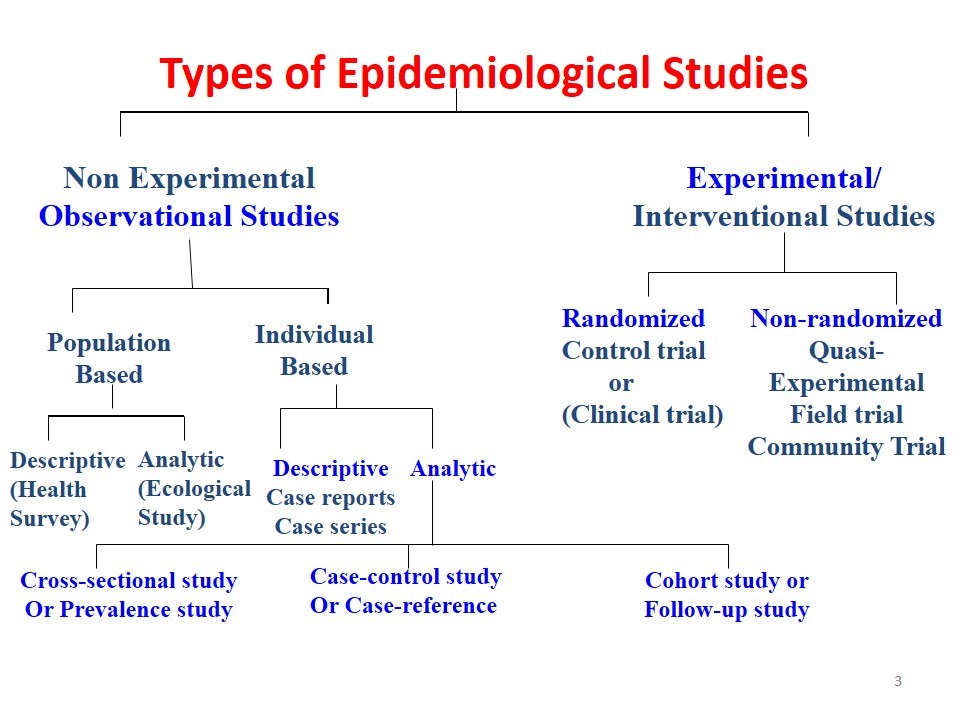

There are several types of epidemiological studies (Figure 1). These fall under experimental and observational designs. The most commonly used analytical study designs are listed here and are covered in this module.

A. Experimental

(i) Randomized clinical trials

(ii) Other non-randomized interventional studies

B. Observational (non-experimental)

(i) Cross-sectional study

(ii) Case control study

(iii) Cohort study

(iv) Ecological study

Figure 1. Types of Epidemiological Studies

Figure from: http://howmed.net/community-medicine/study-designs/

References:

- Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., & Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins

- Gordis, L. (2009). Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders.

NMHRC Dimensions of Evidence

Individual studies included in a systematic literature review should be assessed using the NHMRC dimensions of evidence and provides levels of evidence appropriate for the most common types of research questions. Further information can be found here.

Experimental Study Designs: Randomised clinical trials

![]() Considered the “gold standard” of research designs because provides the most convincing evidence of the relationship between exposure and outcome. Only randomized control trials can fulfill the criteria for causal inference, which means to establish a cause and effect relationship.

Considered the “gold standard” of research designs because provides the most convincing evidence of the relationship between exposure and outcome. Only randomized control trials can fulfill the criteria for causal inference, which means to establish a cause and effect relationship.

One commonly used set of causal inference criteria was proposed by Bradford-Hill.

Bradford-Hill Criteria for Casual Inference1

- Temporal relationship

- Strength of the association

- Biologic plausibility

- Dose–response relationship

- Replication of the findings

- Effect of removing the exposure

- Alternate explanations considered

- Specificity of the association

- Consistency with other knowledge

In a randomized control trial, subjects are enrolled into the study based on a pre-specified set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then subjects are randomized into into one treatment (i.e. treatment group) or a different treatment or placebo (i.e. comparison or control group). This treatment, or exposure, is what you mean to evaluate as the “cause” for a specific outcome. Randomization is hallmark of these experiments and the reason why they are considered the gold standard of scientific evidence. The goal of randomization is to eliminate differences between the groups, or create groups that are as similar as possible. By doing this you remove any bias or confounding that different characteristics of the groups could have on the specific exposure-outcome relationship you are evaluating. After randomization, subjects are followed for a period of time and the incidence of the event that you are interested is measured and compared.

Advantages:

- Gold standard of research designs

- Provides convincing evidence of causal relationship

- High internal validity

Disadvantages:

- Very expensive

- Limited external validity

- Not appropriate for certain questions. Some maybe unethical, cannot be practically carried out, or if rare events are being studied.

- For example, a randomized control trial for the effectiveness of parachutes cannot be conducted. See http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC300808/2

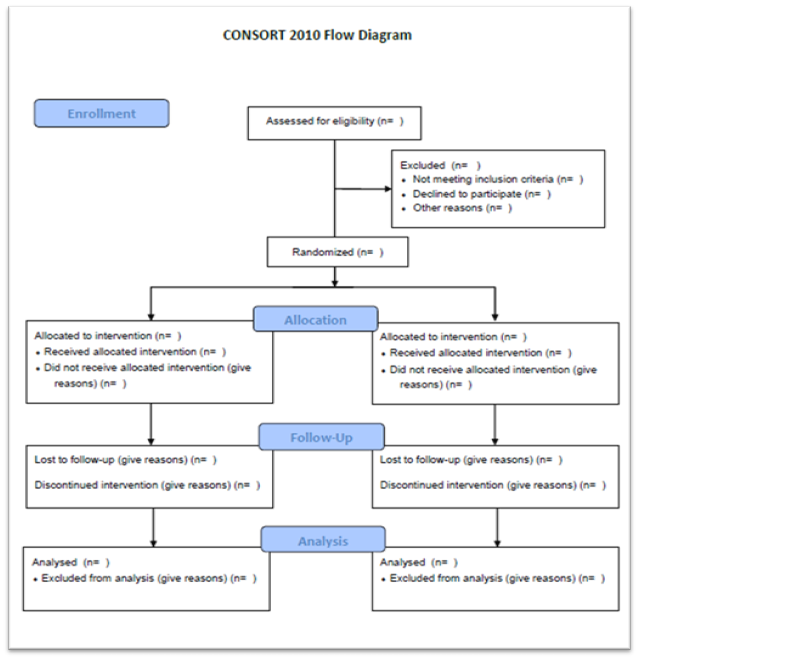

Tip: Become familiar with the CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 guidelines. Figure 1 is the flowchart proposed by the CONSORT 2010 guideline. This flowchart shows the recommended design and structure of a clinical trial. Becoming familiar with this publication guideline is essential for those interested in designing and conducting this type of study.3

Figure 1. CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 guideline Flowchart3

Figure from: http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/flow-diagram

References:

- Austin Bradford Hill, “The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation?,”Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 58 (1965), 295-300.

- Smith , G. C. S. , & Pell , J. P. ( 2003 ). Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials . British Medical Journal , 327 , 1459 – 1461 .

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Ann Int Med 2010;152.

Experimental Study Designs: Other non-randomised interventional studies

Quasi-experiment: In this type of study the exposure is assigned by the investigator, like in a randomized control trial, but the subjects are not randomized.

Quasi-experiment: In this type of study the exposure is assigned by the investigator, like in a randomized control trial, but the subjects are not randomized. - Field trial: Much larger than clinical trials because they study therapeutic interventions. For example, the effect of a new vaccine in the incidence of a particular disease. Because the risk of people to have a particular disease is typically low, to test the efficacy of a vaccine a very large sample of individuals is necessary.

- Community trial: An extension of field trials that involves allocation of treatment to a whole group of people (i.e. community). For example water fluoridation was tested by exposing some communities to it and comparing to other communities without this exposure.

Observational Study Designs: Introduction

![]() Observational studies are studies where the exposure you are evaluating is not assigned by the researcher. This means that no randomization occurs as part of the study and therefore the selection of subjects into the study and analysis of study data must be conducted in a way that enhances the validity of the study.

Observational studies are studies where the exposure you are evaluating is not assigned by the researcher. This means that no randomization occurs as part of the study and therefore the selection of subjects into the study and analysis of study data must be conducted in a way that enhances the validity of the study.

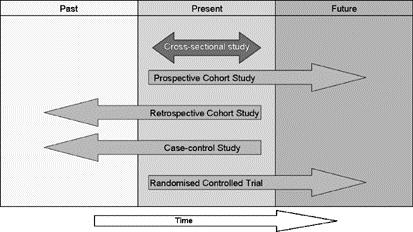

Observational studies can be prospective, retrospective, or cross-sectional. When the exposure was determined can be used to define whether the study is prospective or retrospective. If the exposure was recorded before the outcome occurs the study is typically deemed a prospective study. If the exposure was recorded after the outcome has occurred then the study is typically deemed a retrospective study. A cross-sectional study is one where exposure and outcome are determined at the same time.

The three most common types of observational studies are cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control, which are covered in this document. For other variations and mixed study design please refer to:

- Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., & Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins

- Gordis, L. (2009). Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders.

Figure 1. Direction of temporal observation by study design1

Tip:

Become familiar with the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: http://www.strobe-statement.org/. This is a collaborative initiative of researchers and journal editors involved in the conduct and dissemination of observational studies.1

References:

1.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Annals of internal medicine 2007;147:573-7.

2. Figure from: Levin KA. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-based dentistry 2006;7:24-5.

Observational Study Designs: Cross-sectional study

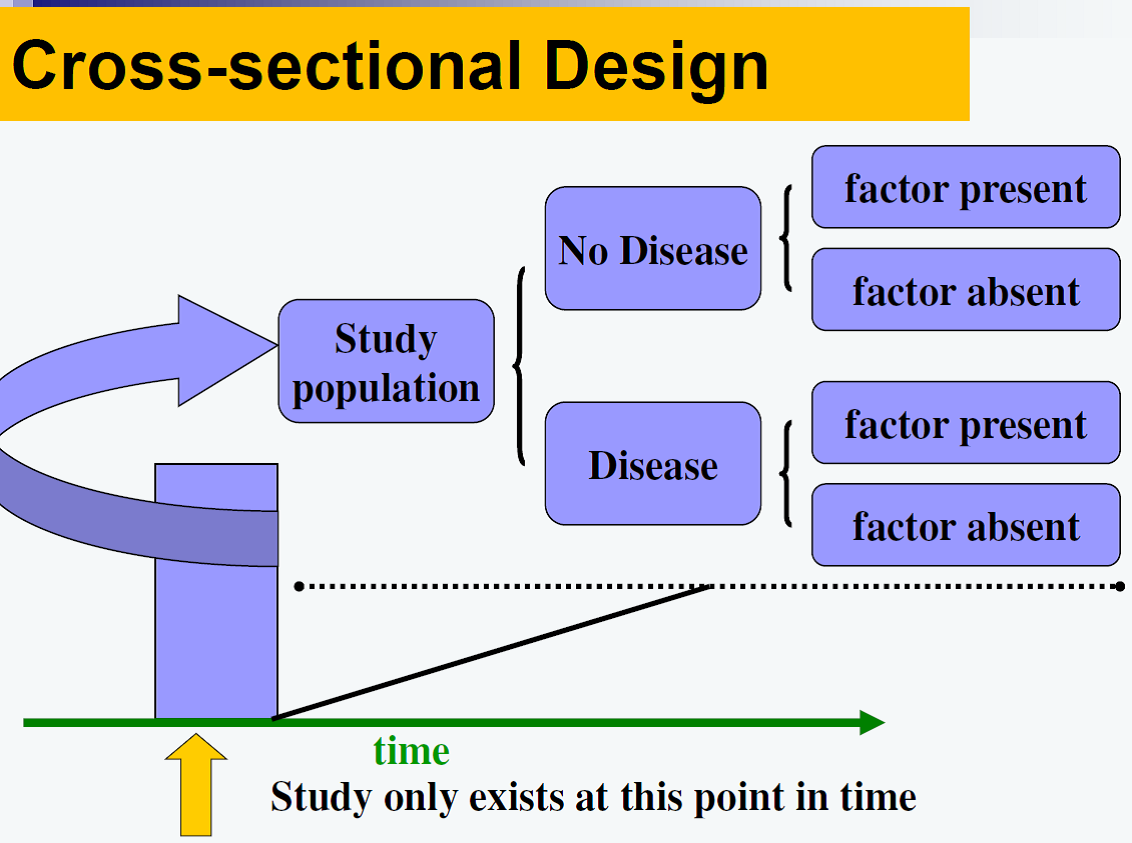

![]() The main purpose of these studies are usually descriptive, but sometimes are carried out to investigate associations between exposures and outcomes. Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of the status of the population at one point in time. With this type of study only the prevalence of conditions can be ascertained (i.e. no incidence can be determined), hence they are also called ‘prevalence studies.’ Because both the exposure and outcome are determined the same time, no temporality between these two variables can be inferred; therefore no inferences about causality can be made from this type of study design.

The main purpose of these studies are usually descriptive, but sometimes are carried out to investigate associations between exposures and outcomes. Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of the status of the population at one point in time. With this type of study only the prevalence of conditions can be ascertained (i.e. no incidence can be determined), hence they are also called ‘prevalence studies.’ Because both the exposure and outcome are determined the same time, no temporality between these two variables can be inferred; therefore no inferences about causality can be made from this type of study design.

A survey is classical example of a cross-sectional study.

Figure 1. Cross-sectional Design

Figure from: Niyonsenga, T. Foundations of Public Health Epidemiology (HLTH 5188). School of Population Health. University of South Australia.

Advantages

- Cheap to conduct

- Not time consuming

- Many outcomes and exposures can be assessed

- Useful for hypothesis generation

- Informative in public health planning (captures disease prevalence)

Disadvantages

- Cannot make casual inferences

- Snapshot of one time point

- Neyman bias- selection bias caused by selective survival in the prevalent cases. Certain exposures with high incidence of death (and quick) will not be captured. Certain exposures that only lead to mild symptoms, and not death, will be over-represented.

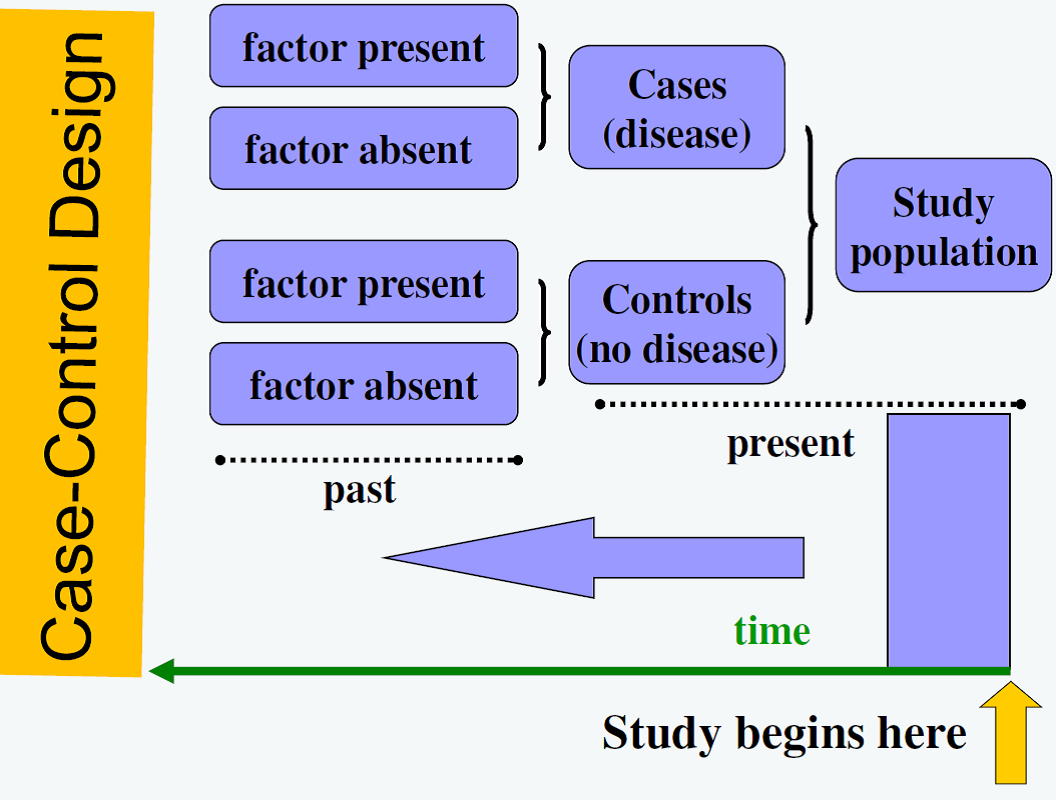

Observational Study Designs: Case control study

![]() Case-control studies can be useful when a rare event is studied, the sample available is small, or when initial evaluation (pilot study) of an exposure of interest is necessary. In these studies, the study sample is selected based on whether the outcome occurred already.

Case-control studies can be useful when a rare event is studied, the sample available is small, or when initial evaluation (pilot study) of an exposure of interest is necessary. In these studies, the study sample is selected based on whether the outcome occurred already.

Subjects with the outcome of interest are referred to as the cases. Controls are subjects without the outcome. Controls must be found based on pre-specified matching criteria. After finding cases and controls, whether or not they had the exposure of interest is determined. Finding appropriately matched controls can be difficult and selection bias must be considered when using this study design.

In this study design, the ascertainment of exposure is done after the outcome. This means results lack the element of temporality and therefore causality cannot be implied from these studies. Case control studies do not answer whether an exposure is associated with an outcome. These studies can only determine whether a subject with the outcome of interest was more/less likely to have the exposure of interest compared to the controls, which makes the level of evidence from this study designs lower than cohort studies.

Figure 1. Case-control Design

Figure from: Niyonsenga, T. Foundations of Public Health Epidemiology (HLTH 5188). School of Population Health. University of South Australia.

Advantages

- Good to investigate rare outcomes

- Good to investigate outcomes with long periods between the exposure and outcome development

- Can be less costly

Disadvantages

- Not good for rare exposures

- They are subject to a lot of bias and confounding

- Difficulties in identifying appropriate controls

- Cannot infer causality because of the lack of temporal association

- Cannot calculate incidence of disease

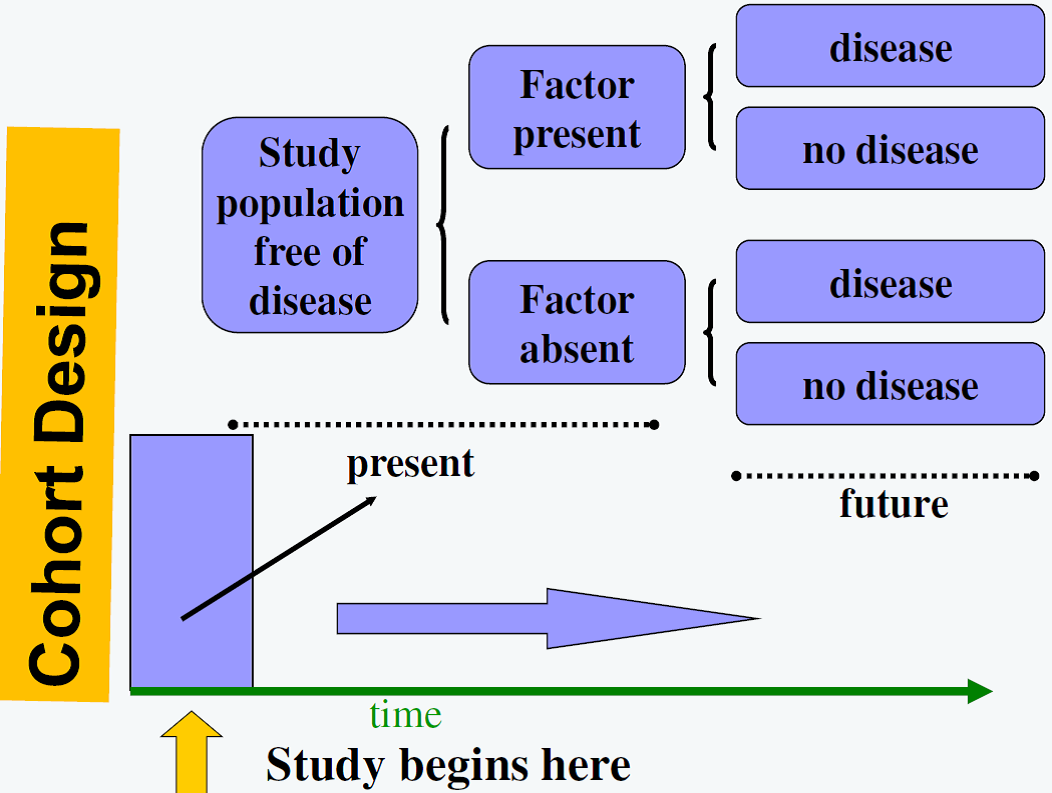

Observational Study Designs: Cohort study

![]() Cohort studies can provide the highest level of evidence, out of the observational studies, regarding the relationship between exposure and outcome. In this type of study the study sample is selected based on the exposure of interest and then moving forward temporally to evaluate the development of a pre-specified outcome. In cohort studies, because the sample is selected based on the exposure, and the outcome occurs at a later date, temporality of the exposure outcome relation is established. In another words, the cause precedes the effect. Cohort studies provide the highest level of evidence that can be obtained from observational data.

Cohort studies can provide the highest level of evidence, out of the observational studies, regarding the relationship between exposure and outcome. In this type of study the study sample is selected based on the exposure of interest and then moving forward temporally to evaluate the development of a pre-specified outcome. In cohort studies, because the sample is selected based on the exposure, and the outcome occurs at a later date, temporality of the exposure outcome relation is established. In another words, the cause precedes the effect. Cohort studies provide the highest level of evidence that can be obtained from observational data.

Figure 1. Cohort Design

Figure from: Niyonsenga, T. Foundations of Public Health Epidemiology (HLTH 5188). School of Population Health. University of South Australia.

Advantages

- Exposure is ascertained before the outcome (establishing temporal relationship)

- Subjects can be selected into the cohort before having the outcome of interest

- Can study several outcome for each exposure

- Incidence of outcome can be measured

Disadvantages

- Expensive (more so in prospective cohorts) and time-consuming

- Inefficient for rare diseases or diseases with long latency

- Loss to follow up (cohort attrition)

- Possible internal validity issues when using secondary data

- Changes in exposure and outcome definitions over the years can impact study

Observational Study Designs: Ecological study

![]() This type of observational study uses aggregate level exposures and outcomes. The unit of observation is aggregate (i.e. cities, decades, countries) and no individual level data is available. They are useful to monitor population health, help with public health planning, and make large scale comparisons. These studies can be cheap and easy to conduct, typically because they use existing data sources but they can suffer from a unique type of bias, called Ecological Fallacy. This fallacy is the assumption that what is seen for the aggregate level holds true for individuals, when in fact it does not.

This type of observational study uses aggregate level exposures and outcomes. The unit of observation is aggregate (i.e. cities, decades, countries) and no individual level data is available. They are useful to monitor population health, help with public health planning, and make large scale comparisons. These studies can be cheap and easy to conduct, typically because they use existing data sources but they can suffer from a unique type of bias, called Ecological Fallacy. This fallacy is the assumption that what is seen for the aggregate level holds true for individuals, when in fact it does not.

For More Information on Study Designs

- Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., & Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins

- Gordis, L. (2009). Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders.

- Porta, M. (2014). A dictionary of epidemiology, 5th edition. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. Available at: http://www.irea.ir/files/site1/pages/dictionary.pdf

- Friedman L., et al. (2015). Fundamentals of Clinical Trials, 5th edition. Springer. Available at: http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-18539-2

- Hulley S., et al (2015). Designing Clinical Research, 4th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Online Videos and Other Resources:

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice, Third Edition An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics: http://www.cdc.gov/ophss/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section7.html

- Intro to Epidemiology Study Designs:

- Epidemiology Study Types: Cohort and Case-Control:

- Epidemiology Study Types: Randomized Control Trial:

- On intervention studies: https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/epi/cancerepi/CancerEpi-7.pdf

- On ecological studies:

- Levin KA. Study Design VI:Ecological Studies. Evid-based Dent 2006;7:10. http://www.nature.com/ebd/journal/v7/n4/full/6400454a.html

- http://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/epidemiology-uninitiated/6-ecological-studies

- https://onlinecourses.science.psu.edu/stat507/node/4