How students learn

| Site: | learnonline |

| Course: | Teaching and learning in Health Sciences |

| Book: | How students learn |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 27 February 2026, 1:33 PM |

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Introduction

In order to get the best results from your teaching endeavours, it is helpful to have a idea of the theory and practice behind student learning.

In this Moodle 'book', you will see various 'chapters' outlining some of the principles behind student learning, which you can use to underpin your course learning and assessment strategies, and some practical approaches to developing effective learning activities.

Just click on the table of contents to the left to go to the different 'chapters', or use the arrows at the top and bottom of each page to move back and forwards in this book. You can also print the book or any of the chapters out, using the links in the Administration block to the left.

Two very important learning theories to check out are constructivism and student-centered learning - you can find more information from the chapters to the left.

We have also included information on other popular theories about how students learn best, such as:

- Active learning - in which students solve problems, pose and answer questions, discuss and debate

- Cooperative learning - in which students work with their peers in on projects which foster positive interdependence and individual accountability

![The learning pyramid [Source: http://www.uinjkt.ac.id/en/student-centered-lerning/] The learning pyramid [Source: http://www.uinjkt.ac.id/en/student-centered-lerning/]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916023/mod_book/chapter/101848/Resource%201.jpg)

Interesting links

The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice

Practitioner Guide from the Innovative Learning Environments Project. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

Constructivism

Constructivist learning theory emphasizes the learner's critical role in their own learning.

The idea of constructivism is that every student 'constructs' his or her knowledge and understanding by reflecting on their own experience. They make sense of their experience by forming 'mental models'. Therefore, when we learn, we are really finetuning and honing those models, to align to this new experience.

There are several guiding principles of constructivism:

1. Learning is searching for meaning. The aim is for the student

to construct his or her own deep meaning, not just memorize the 'right' answers

or quote somebody else's meaning. Therefore, teaching should start with looking

at the issues for which the students are trying to construct meaning.

2. Real

understanding means understanding the whole theory, the subordinate parts, and

how they all fit together.

3. In

order to teach well, we must understand what mental models our students use to

view the world, and what assumptions they make to support those models.

4.

Assessment needs to be part of the learning process, so that it gives students

feedback on the quality of their learning.

Information and image sourced from https://www.funderstanding.com/theory/constructivism/#sthash.Ms3nSyNt.dpuf

![Constructivism concept map [Source: http://constructivism512.pbworks.com/w/page/16397300/Constructivism%20Concept%20Map]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916023/mod_book/chapter/102052/Resource%202.jpg)

Interesting resources

Brandon, A & All, A 2010, 'Constructivism theory analysis and application to nursing programs', Nurse Education Perspectives, vol. 31(2), pp. 89-92.

Candela, L, Dalley, K & Benzel-Lindley, J 2006, 'A case for learning-centered curricula', Journal of Nursing Education, vol. 45(2), pp. 59-66.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

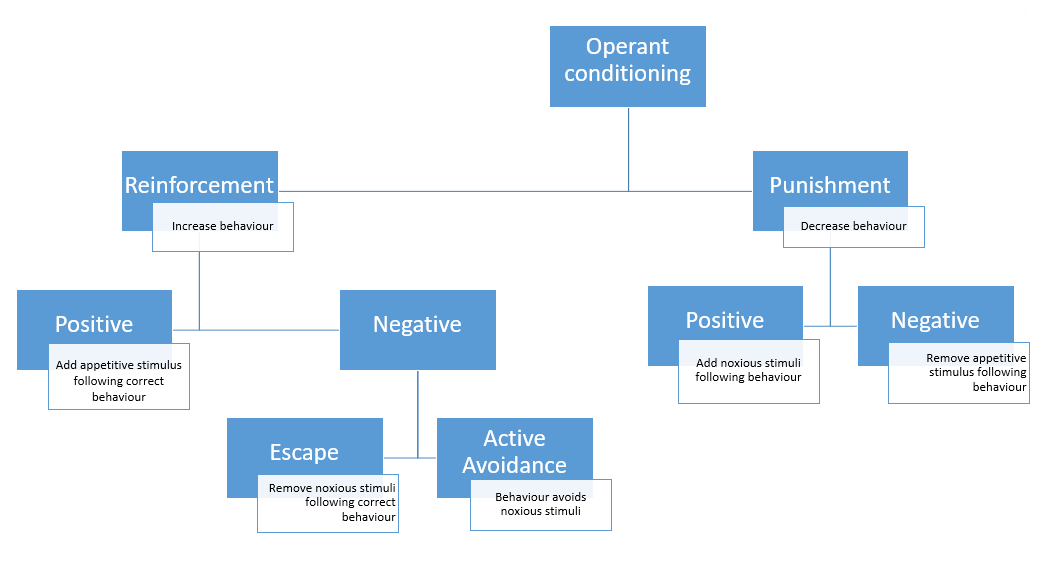

Behaviourism

The basis of the behaviourism is the theory that humans can be trained to produce certain behaviour in response to certain stimuli, and the more often the response is stimulated, the stronger is the training.

In more advanced theories of behaviourism, reinforcement is seen

as the focus, and the idea is that the right applications of negative and

positive reinforcement will result in student learning (Skinner’s operant conditioning).

Behaviourism has had a bad rep for a long time, because it's opften viewed as a low level approach to training and education, that relies on just producing a behaviour - an external response - without considering the internal processes that produce the behaviour. Many people see this as being on the same level as training a dog, without any consideration of free will and choice.

However, there's no denying that throughout our lives (especially when we are very young), we learn a lot of what we know from the stimulus-response model.

Skinner noted that behaviorism is often is used by school teachers, who reward or punish student behaviours (Funderstanding, 2002).

In fact, the premise underlying much authored elearning is based on the concept of rewarding correct answers - which is a form of behaviourism, but at a higher level.

Information processing

The information processing theory is based on the idea that humans actively process the information they receive from their senses, like a computer does. Learning is what is happening when our brains recieve information, record it, mould it and store it.

![information processing model [Source: http://dataworks-ed.com/the-information-processing-model/]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916023/mod_book/chapter/120209/info%20processing%20model%20b.png)

In information processing theory, as the student takes in information, that information is first briefly stored as sensory storage; then moved to the short term or working memory; and then either forgotten or transferred to the long term memory, as:

- semantic memories (concepts and general information)

- procedural memories (processes)

- images

For learning to occur, it's critical that information is transferred from the short term memory to the long term memory, because if we have more than seven pieces of information in our short term memory at one time, we get an overload (referred to as cognitive overload).

So how to we avoid cognitive overload with students? If teachers prioritizing the information they give students, they help students to work our the critical elements of the information.

Make sure you have the students’ attention, and help students to make connections between new material and what they already know. (Image here adapted from Cognitive Approach to Learning.)

Include lesson time for repetition and review of information, present material in a very clear manner, and focus on the meaning of information.

Download document Helping students memorise: Tips from cognitive science

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

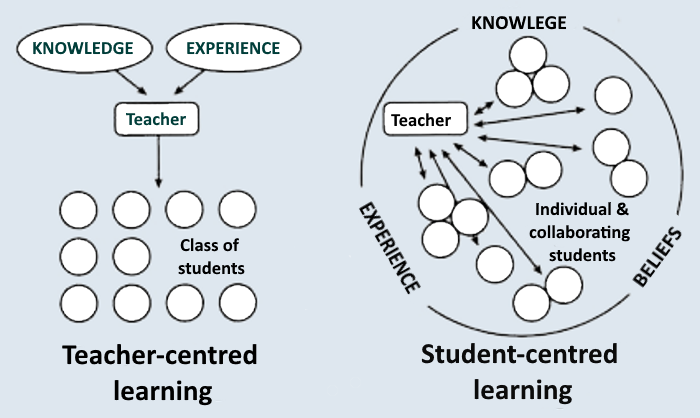

Student-centered learning

"... what the student does is actually more important in determining what is learned than what the teacher does." Thomas Shuell

One of the most effective ways to optimise how and how much students actually learn from a teaching activity is to use student-centered learning strategies, which are based on the theories of constructivism.

Most modern tertiary institutions actively practice teaching which encourages students to take an active role in creating the learning and assessment processes (or say they do, anyway)

Student-centered learning strategies shift the focus of an activity from the teacher to the students. They're very relevant to tertiary and professional education, because they foster motivation and incentive to learn. These types of approaches emphasise the students' interests, abilities and learning styles.

If the teacher is a facilitator, guiding the students, rather than an instructor, giving them directions, then that teacher is allowing the learners themselves to take an active part in deciding what they learn, how they learn, and how they can evaluate what they have learnt.

The aim is for learners to take more responsibility for their learning, and 'own' it, rather than just sitting waiting for the teacher to 'fill them up' with knowledge.

There is evidence that student-centered learning in university helps students to become independent problem solvers, and improves their critical and reflective thinking. It also increases their own confidence in their understanding and their skills.

The input which the students have into their learning also has implications for assessment. Students will be more involved in deciding how to evaluate and demonstrate their learning.

Putting it into practice

Learning contracts are mutual agreements between teachers and students which state explicitly what a learner will do to achieve specific learning outcomes, and how their learning will be measured and evaluated.

They foster an increased responsibility for their own learning. Contracts can include learning expectations, learning resources, learning experiences, documentation and other information such as designated evaluators, evaluation criteria and timelines.

Source: Teaching Strategies Promoting Active Learning in Healthcare Education

Interesting resources

Azer, S 2013, Making sense of clinical teaching: A hands-on guide to success, Boca Raton, CRC Press/Taylor & Francis.

Bradshaw, M & Lowenstein, A 2014, Innovative teaching strategies in nursing and related health professions, Jones and Bartlett Learning.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Active learning

In active learning, the teacher provides activities that promote analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of the course content. When students are actively engaged, they think deeper about the course content, and they enjoy their learning. Their higher order thinking is advanced is they are actively participating in and reflecting on the learning activities.

There are several other learning styles which are associated with active learning - for example, 'cooperative learning', and 'problem-based learning'.

![Active learning pyramid [Source: http://plpnetwork.com/2015/03/10/shift-active-learning-technology-answer/]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916023/mod_book/chapter/101290/Active%20learning.png)

There are a range of activities which can promote active learning: case studies, simulations, discussion, problem solving, group work, project work, interactive online activities, peer teaching, and so on. When setting learning activities, the key principles to keep in mind are:

1. Set tasks which have purpose and relevance to the students.

2. Encourage students to reflect on the meaning of what they have learnt.

3. Allow students to negotiate goals and methods of learning with the teacher.

4. Encourage students to critically evaluate different ways and means of learning the content.

5. Set learning tasks with the same level of complexity as in professional contexts and real life.

6. Keep tasks situation-driven: that is, consider the need of the situation.

Adapted from Barnes, D 1989, Active Learning, Leeds University TVEI Support Project.

Putting it into practice: Applications in Health Sciences

1. Health educators can use questioning strategies to develop

critical thinking, decision making, and problem solving in students. Word your

questions so that they challenge the students to use a higher level of

cognitive development (analysing, evaluating and creating). For example,

asking a student to define a type of x-ray would test their ability to remember,

but asking a student to assess a request to perform that x-ray on a patient

with particular symptoms would test ability to evaluate, and prompts the

student to think more deeply about the material.

2. Self-evaluation is a type of self-directed learning which allows students to assess their own performance. As a result, they become more independent, and are able to identify knowledge and understanding weaknesses. The aim of the self-evaluation activity is to assist students to identify strengths and weaknesses in their learning, to set their own performance goals, and to increase their satisfaction with their learning - all key elements of the clinical and professional work environments. However, be aware that students can tend to be overly critical of their own performance

Adapted from https://www.scribd.com/document/271833630/Teaching-Strategies-Promoting-Active-Learning-in-Healthcare-Education

Interesting resources

Wilson, L & Rockstraw, L 2012, Human simulation for nursing and health professions, Springer Pub Co, New York, NY.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Collaborative learning

Collaborative learning encompasses a whole host of approaches which use the group and team approach for student work. Another term associated with collaborative learning is peer learning, in which students learn from and teach each other.

Well planned group work activities can result in students work together to accomplish a common academic goal - this is cooperative learning. It's also important to remember that teamwork is a skill much prized in industry ... but it needs to be carefully set up and prepared.

Examples of collaborative learning activities which can be very effective in the classroom include:

- group problem-solving tasks;

- team writing assignments, so that a group can submit a cooperatively-authored document

- reciprocal teaching, in which students act as teachers to lead discussion, summarize material, ask questions, and clarify material.

When you plan collaborative learning activities, think carefully about the goals of the activity, to make sure that there is sufficient 'depth' for each group member to have meaningful input.

Try to shape the activity to allow for various group personalities (such as the creative contributers, finishers, etc) each to have the opportunity to shine. Note that you will need to work out how to fairly assign marks to the final product. The self and peer assessment strategy, in which students assess each others' contributions using a list of criteria, may help here, especially if the students have been involved in establishing the criteria used.

Remember that most students won't automatically know how to work together productively in groups, and some of them might be reluctant initially. They need to be taught the skills they need to maintain a 'positive inter-dependence', in which each student depends on the others for success, while maintaining individual accountability.

Setting up the groups must also be done carefully - groups that are randomly assigned don't alway succeed. Pay attention to social skills and group processing.

A number of collaborative teaching spaces have been set up throughout the UniSA campuses, in which the physical layouts and technical sharing functions have been especially created to optimise group work and collaborative learning. At the City East campus, there are two Collaborative Teaching Spaces: in the library, in room C4-08, and room C6-26. You can see an image of room C4-08 below.

Putting it into practice: Examples of successful collaborative learning in Health Sciences

Collaborative learning in the health sciences can be used in the context of student placement. Groups can be arranged for students to come together to reflect on, and find possible solutions to, any issues that arise on their placement.

The teacher should act as a facilitator if only to encourage all students to find their voice and ensure that the potential solutions that arise are acceptable solutions for the problems faced. Students should collectively problem-solve, drawing on their own experiences, learning and understanding to create better outcomes.

(Adapted from: Myron, R, French, C, Sullivan, P, Sathyamoorthy, G, Barlow, J & Pomeroy, L 2018, 'Professionals learning together with patients: An exploratory study of a collaborative learning Fellowship programme for healthcare improvement', Journal of Inter-professional Care, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 257-265.)

Another example of cooperative learning is adopting a team approach to learning a particular concept. The concept could be broken down in to sections whereby each member of the team needs to learn and become the ‘expert’ of a particular section.

The ‘expert’, once mastering the content, needs to identify an effective way to engage and instruct the group, so they too can become ‘experts’. This strategy requires the student to teach others, an active learning strategy that achieves higher information retention rates than more passive learning strategies.

(Adapted from: Cinelli, B, Symons, C, Bechtel, L & Rosecolley, M 1994, 'Applying cooperative learning in health-education practice’, Journal Of School Health, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 99-102.)

Interesting resources

Sydney University: Self and Peer Assessment

A team-based learning guide for students in health professions education

Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Thinking and mind tools

Thinking tools can provide a scaffold to help students to think with more depth and structure, and can be very valuable in giving students a framework for individual and group problem solving.

There are many examples of thinking and mind tools which can be effectively used in educational contexts: for example, you've probably heard of the de Bono 6 Hats thinking strategy, and everyone's heard of brain-storming.

It's important to select the right tool for the particularly educational activity, and to scaffold the students' use of the tool carefully. You'll probably find that an approach which works well in one context is not really effective in another - keep careful note of what works with your students at various levels and in a range of problem solving activities.

We have prepared a resource which outlines the use of a number of thinking tools, including:

- Y charts

- PMI charts

- De Bono's 6 Hats

- 3-2-1 Thinking

- Brainstorming

In this resource, you'll see guidelines on best use of the tool in teaching, ideas on putting the tool into practice in Health education, and links to further resources.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Cognitive theory of multimedia learning

“People learn more deeply from words and pictures than from words alone”.

The quote above is true ... however, it's important to remember that just putting text and pictures together doesn't necessarily make for effective learning.

If you are using a variety of media in your teaching (test, images, video, interaction), you need to consider the best way for students to learn.

The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning gives guidance for informed multimedia instructional messages. This theory is based on three assumptions:

- Every humans has two separate channels for processing visual and auditory information (dual channels)

- Humans can only process a certain amount of information in each channel at one time (that is, they have limited capacity)

- Humans learn actively by paying attention to incoming information, organising selected information into undertandable mental representations, and integrating those representations with other knowledge (active processing)

For example, if a student is presented with an auditory information display (narration) at the same time as a visual information display (text), then the student will need to process this information using both channels.

However, in accordance with Priniple 2 above, the student's ability to process is limited. Therefore, the student's brain is forced to be selective with the information it chooses to keep, and which bits of information to make connections between.

Putting it into practice: Instructional goals for multimedia instruction

The table below offers a brief overview of three instructional goals in multimedia learning, bearing in mind the assumptions we discussed above.

You might find it useful to consider the various techniques listed in the third column when creating a multimedia learning activity.

|

Goal |

Representative technique |

Description of technique |

|

Minimize extraneous processing |

Coherence principle |

Eliminate extraneous (non-relevant) material |

|

|

Signaling principle |

Highlight essential material |

|

|

Redundancy principle |

Do not add printed text to spoken text |

|

|

Spatial contiguity |

Place printed text near corresponding graphic |

|

|

Temporal contiguity principle |

Present narration and the corresponding graphic simultaneously |

|

Manage essential processing |

Segmenting principle |

Break a presentation into parts |

|

|

Pre-training principle |

Describe names and characteristics of key elements before the lesson |

|

|

Modality principle |

Use spoken rather than printed text |

|

|

Multimedia principle |

Use words and pictures together rather than words alone |

|

Foster generative processing |

Personalization principle |

Put words in conversational style |

|

|

Voice principle |

Use human voice for spoken words |

|

|

Embodiment principle |

Give on-screen characters humanlike gestures |

|

|

Guided discovery principle |

Provide hints and feedback as learner solves problems |

|

|

Self-explanation principle |

Ask learners to explain a lesson to themselves |

|

|

Drawing principle |

Ask learners to make drawings for the lesson |

Interesting resource

Mayer, R 2014, 'Cognitive theory of multimedia learning', Richard Mayer, The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 43-71