| Ask us |

Tell us |

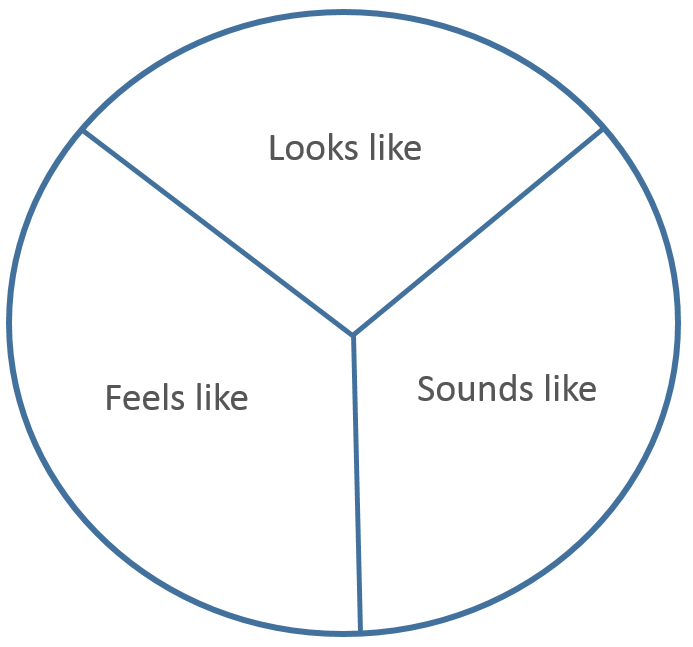

The Y Chart

The aim of the Y Chart is for students to think about environments from three perspectives.

- Looks like ...

- Sounds like ...

- Feels like ... (Usually this is the sensory 'feel', not the touchy-feely emotional 'feel'; but sometimes things do have a feel that triggers emotional responses which are worth exploring.)

If it's appropriate to the content, you can also add a fourth perspective of Smells or Tastes like (forming an X chart).

It takes more than knowledge and practice to change a novice into an experts. Students become aware of the information being fed into their brains by their senses. This means not just 'seeing' but consciously observing, not just hearing but actively 'listening', etc.

These charts are great ways to get students thinking in depth about concepts and situations, because they move from the concrete to the abstract. It encourages them to produce a range of adjectives which can define and scope a concept.

To do this properly, they'll need to think deeply about not just the whats but of the whys. It is particularly useful in the early stages of a task, to explore and define the task requirements.

Before beginning any group work in the classroom a Y chart could be developed on effective group work; thus setting the scene for the expectations of cooperation and teamwork whilst working in groups.

Download a template (73 KB)

Putting it into practice: Application in Health Sciences

Consider a clinical environment. An expert moves into a clinical space and very quickly forms an opinion over whether that space is operating appropriately.

For example, if a patient has a condition like asthma ... what would the expert expect to hear, see and feel?

Sometimes experts may become aware of problems without even being quite sure why, or what the problem is; so they stop and look, listen, and think. They are taking in and processing information through all their senses. Somewhere during that cognitive processing, using sensory information, they identify the problem they have noticed.

This happens with people who have considerable experience to draw upon. The problem is we can't easily teach the skill; partly because we are not always aware that we are doing it, and partly because that is just not what we do. We teach skills in isolation, even if we do it in situ.

Asking the students questions such as, "What does a properly operating ward look like, sound like, and feel like", forces them to step back and think about the whole. What is it that makes a ward function?

Also consider this example from the education sphere:

From the teacher's perspective, what does a properly functioning class look like and sound like?

It has a low murmur; not quiet but not loud. The teacher can't be heard from the hallway.

What does it look like? The desks are in groups. Work is displayed so that the space is 'owned' by the students: not just the best work, but everybody's. Resources are where students can access them, unless they are dangerous.

There are a few, clearly-displayed rules; they are at the principle level, not the instructional level, and have been jointly agreed.

And so on ...

Interesting resources

Herrington J, Reeves, T, Oliver, R 2013, Authentic Learning Environments in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, pp 401-412.

Barrows, S 2006 Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview