Design and teach a course

| Site: | learnonline |

| Course: | Teaching and learning in Health Sciences |

| Book: | Design and teach a course |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 7 March 2026, 8:11 AM |

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

The overview of curriculum

Below, you'll see three lenses to look at curriculum. (Note that there may be differences in terminology between education systems and institutions, but the terms broadly mean the same thing.)

.

Intended Curriculum

This is the curriculum we plan for. It's what's meant to happen in the classroom. When we talk of 'alignment' - be it horizontal or vertical - we're talking in the first instance of the intended curriculum.

Enacted Curriculum

This is the curriculum that actually happens in the teaching space (virtual or face to face).

Of course, in a perfect world, 'intended' would be the same as 'actual', but this doesn't really happen very often. If a course has 20 tutors teaching into it, there will probably be 20 slightly different versions of enacted curriculum. There are lots of possible reasons for this ... tutors may interpret teaching points differently, or they may - for some reason - decide to teach something else, or the session objectives may be vague, or the tutor may need to adjust the curriculum for students who aren't ready, and on and on.

Just to be clear, this is not necessarily about tutors doing different things. It's quite possible for even different activities to result in the same curriculum or the same learning objectives. So it's not about the activity in isolation. It is about the purpose and learning that is meant to derive from the activity. Using the same logic it is quite possible the SAME activity will result in a different curriculum and different learning objectives. It's about the learning, not the teaching. (IMage to the right sourced from Shutterstock Photo Library, used through a UniSA subscription).

.

Hidden Curriculum

This is the most problematic of the three lenses. The hidden curriculum is what the student actually learns. This is not just about learning you can measure, but unintended learning as well.

For example, if lecturers ask students to do a reading, and they don't, and then there are no consequences, students learn not to bother with readings. If teachers say they're interested in student thinking, but then give students no opportunity to input, or don't appropriately acknowledge their input (over-riding their answers, for instance), they learn to just tell us what we want to hear.

One of the few ways we can find out about the hidden curriculum is through evaluation. Course Evaluation Instruments, for all their negatives, are a chance for us to learn about the hidden curriculum. However, it's better to actually learn about this before the end of the course through a CEI - formative ongoing evaluation is a better idea!

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

How students learn

In order to get the best results from your teaching endeavours, it's helpful to have a idea of the theory and practice behind student learning.

We have prepared a resource which presents a range of principles behind student learning.

You can use this to underpin your course learning and assessment strategies, and some practical approaches to developing effective learning activities.

Just click on the particular principle below to go to the relevant resource page:

- Constructivism

- Behaviourism

- Information processing

- Student-centred learning

- Active learning

- Collaborative and peer learning

- Thinking and mind tools

![The learning pyramid [Source: http://www.uinjkt.ac.id/en/student-centered-lerning/] The learning pyramid [Source: http://www.uinjkt.ac.id/en/student-centered-lerning/]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916132/mod_book/chapter/138327/Resource%201.jpg)

Image sourced from https://sites.google.com/site/pedagogiayandragogia2016/the-learning-pyramid.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Aligning your course to the program

Unlike horizontal alignment, which has remained pretty much unchanged since people started writing about curriculum, vertical alignment is relatively new. That is not to say people didn't do it in the past, but it wasn't formally captured.

The emergence in importance of the AQF and TEQSA have created an environment that requires us to formalise the curriculum vertically.

Vertical alignment is the alignment of the whole education system, relative to the in which context you're teaching. For we at UniSA, that means not just 'university' but it includes external bodies like the AQF, registration bodies, industry bodies, or any stakeholder whose perspective needs to be incorporated.

The discussions and requirements of AQF / registration bodies / academia result in a set of outcomes that are required for a graduate to be recognised. The vertical alignment is the way these requirements feed through the program in an intentional and explicit way. If you are a Program Director, you will be involved intimately in the discussions with registration bodies to create the program objectives.

The practical implication of all this is to design the three years of a program so that the program will build students' knowledge, skills and attitudes, and enable them to meet the program objectives. Further, it means COURSES must belong to PROGRAMS, not to the people who run the course. There needs to be some certainty that courses deliver what is needed to build on previous knowledge, and creating a platform for subsequent courses.

The image below captures this really well.

Unlike horizontal alignment, which has remained pretty much unchanged since people started writing about curriculum, vertical alignment is relatively new. That is not to say people didn't do it in the past, but it wasn't formally captured.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Setting your course to the appropriate level

Horizontal alignment is the degree to which assessment matches the corresponding content standards for a subject area at a particular grade level.

Horizontal alignment is the degree to which an assessment matches

the corresponding content standards for a subject area at a particular grade level

(Porter, 2002; Webb, 1997a; Webb, 199

In terms that we use at UniSA, it means:

- aligning the assessment to the course objectives, and making sure that it is at an appropriate level, and

- delivering the course content which has been decided in the program design, and for which your course has been vertically aligned.

- Assessment, in terms of alignment, is about evidence. That is, it is evidence that a student has obtained a level of competence in relation to one or more course objectives. The assessment needs to be supported by appropriate activities at course level.

- Activities relates to students engaging in the types of activities that will allow them to prepare for the assessment that will demonstrate competence against an objective. Think here not just about cognition, but about the full range of activities the student will need. For example, if the assessment asks for a report, then you need to make sure that the students can already write a report. If not, then you need to teach them.

If we had a simple, flat curriculum, such as you would see in a primary school, the vertical alignment would be how the grades aligned up (Reception to year 7), and the horizontal alignment would be alignment within a grade.

But at University, we have such a complex, flexible and dynamic learning environment that we have to be careful about what we claim are connections at the same year level. For example, although two courses may be delivered in first year, we would expect to have some learning areas deliver higher learning outcomes in an SP5 course than an SP2 course (and we would have planned for this in our vertically alignment).

When you consider we have seven different study periods, electives, core courses that run across multiple programs, course streams, and so on ... you can see that horizontal programming outside the boundaries of a course is problematic.

If we had a more simplistic study year (for example, with no study periods), some really interesting horizontal alignment ideas might become more realistic. For example, it might be possible to move from a course-based approach to a 'theme' approach, to learning which encourages thinking about trans-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary learning.

If you were to consider teaching from a research perspective, a reasonable equivalent of alignment would be;

- Objective = hypothesis

- Assessment = evidence

- Activities = method of data collection

You would then ask, "Is there sufficient evidence for the hypothesis to be validated?"

.

Where horizontal alignment often goes wrong ...

There are three major areas where horizontal alignment might go wrong.

- Mismatching the learning objective verb to the intent of the learning objective. Beware of learning designed specifically to focus on a higher order form of thinking; for example, learning about analysis is not analysis.The higher verb kicks in when the students perform the verb. A competent level of 'analysis' can't be assessed by retelling, understanding, or at any level that is not at least 'analysis'. The complexity of analysis at P1 might be quite basic but it would still be 'analysis'. You will see this in many rubrics where a P1 is awarded against a criteria that reads something like "the student conveys a basic understanding of the topic". This might really mean something like "the student has analysed the 'x' to a basic level making few links between sections"...

- Curriculum obesity - this means that there is lots and lots of content not connected to any learning objective.

- Curriculum delinquency - this means that the curriculum is not aligned very well. A good instance of this is how we often ask students to perform at a much higher cognitive level than the objective states. For example, an objective that says "understand" is not going to be aligned to an assessment which involves writing an essay. Essays argue, they present a case and that requires analysis and evaluation and maybe synthesis.

Adapted from Case, B. & Zucker, S 2008, Policy Report: Horizontal and Vertical Alignment, San Antonio, pp. 1–6.

Horizontal and vertical alignment tools and Bloom's taxonomy

There are a number of taxonomies that provide

effective structures for designing alignment. You can see more detail about

these taxonomies (also often called 'models') in the table of contents to the

left.

However, most of the models are founded in the most famous of all - Blooms Cognitive taxonomy. This taxonomy was produced by a group which also produced two other taxonomies: the Affective domain taxonomy, and the Psycho-motor domain taxonomy. The differences between the three are toulined below:

- The cognitive domain is about thinking / conceptualisation (see Anderson's taxonomy below).

- The affective domain deals with ethics, values and behaviours, which are very hard to measure.

- The psycho-motor domain deals with motor / muscular skills and things like dance and creative movement

The image to the right is sourced from https://serc.carleton.edu/details/images/7767.html.

Bloom's cognitive domain (Bloom's Taxonomy 1956)

- Knowledge: Remembering or retrieving previously learned material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: know, identify, relate, list, record, name, recognize, acquire

- Comprehension: The ability to grasp or construct meaning from material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: restate, locate, report, recognize, explain, express, illustrate, interpret, draw, represent, differentiate

- Application: The ability to use learned material, or to implement material in new and concrete situations. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: apply, relate, develop, translate, use, operate, practice, calculate, show, exhibit, dramatize

- Analysis: The ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components so that its organizational structure may be better understood. Examples of verbs that relate to this function re: analyze, compare, probe, inquire, examine, contrast, categorize, experiment, scrutinize, discover, inspect, dissect, discriminate, separate

- Synthesis: The ability to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: compose, produce, design, assemble, create, prepare, predict, modify, tell, propose, develop, arrange, construct, organize, originate, derive, write, propose

- Evaluation: The ability to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: judge, assess, compare, evaluate, conclude, measure, deduce, validate, consider, appraise, value, criticize, infer

.

Bloom's affective domain

|

Category or 'level' |

Behavior descriptions |

Examples of experience, or demonstration and evidence to be measured |

'Key words' (verbs which describe the activity to be trained or measured at each level) |

|

1. Receiving |

Open to experience, willing to hear |

Listen to teacher or trainer, take interest in session or learning experience, take notes, turn up, make time for learning experience, participate passively |

Ask, listen, focus, attend, take part, discuss, acknowledge, hear, be open to, retain, follow, concentrate, read, do, feel |

|

2. Responding |

React and participate actively |

Participate actively in group discussion, active participation in activity, interest in outcomes, enthusiasm for action, question and probe ideas, suggest interpretation |

React, respond, seek clarification, interpret, clarify, provide other references and examples, contribute, question, present, cite, become animated or excited, help team, write, perform |

|

3. Valuing |

Attach values and express personal opinions |

Decide worth and relevance of ideas, experiences; accept or commit to particular stance or action |

Argue, challenge, debate, refute, confront, justify, persuade, criticize, |

|

4. Organizing or Conceptualizing Values |

Reconcile internal conflicts; develop value system |

Qualify and quantify personal views, state personal position and reasons, state beliefs |

Build, develop, formulate, defend, modify, relate, prioritize, reconcile, contrast, arrange, compare |

|

5. Internalizing or Characterizing Values |

Adopt belief system and philosophy |

Self-reliant; behave consistently with personal value set |

Act, display, influence |

Adapted from http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/affective/index.html

The psychomotor domain

Bloom never completed the Psychomotor Domain. The most recognised version (below) was developed by Ravindra H. Dave.

|

Category or 'level' |

Behavior Descriptions |

Examples of activity or demonstration and evidence to be measured |

'Key words' (verbs which describe the activity to be trained or measured at each level) |

|

Imitation |

Copy action of another; observe and replicate |

Watch teacher or trainer and repeat action, process or activity |

Copy, follow, replicate, repeat, adhere, attempt, reproduce, organize, sketch, duplicate |

|

Manipulation |

Reproduce activity from instruction or memory |

Carry out task from written or verbal instruction |

Re-create, build, perform, execute, implement, acquire, conduct, operate |

|

Precision |

Execute skill reliably, independent of help, activity is quick, smooth, and accurate |

Perform a task or activity with expertise and to high quality without assistance or instruction; able to demonstrate an activity to other learners |

Demonstrate, complete, show, perfect, calibrate, control, achieve, accomplish, master, refine |

|

Articulation |

Adapt and integrate expertise to satisfy a new context or task |

Relate and combine associated activities to develop methods to meet varying, novel requirements |

Solve, adapt, combine, coordinate, revise, integrate, adapt, develop, formulate, modify, master |

|

Naturalization |

Instinctive, effortless, unconscious mastery of activity and related skills at strategic level |

Define aim, approach and strategy for use of activities to meet strategic need |

Construct, compose, create, design, specify, manage, invent, project-manage, originate |

Adapted from http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/psychomotor_domain.html

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Anderson's Taxonomy

Anderson's taxonomy was developed directly from Bloom's Cognitive taxonomy, with three important differences:

- Bloom uses nouns, and Anderson uses verbs. This is important because it affects the way we demonstrate these abilities as things we perform.

- The Anderson taxonomy introduces the idea of creativity, and puts it at the very top, the highest form of learning.

- There is some relatively minor reshuffling of taxonomic levels.

Warning: Bloom's and Anderson's taxonomies are so interwoven they are sometimes presented as the same. Actually, Anderson's is sometimes referred to inaccurately as Bloom's. You don't ever see Bloom's referred to as Anderson's!

|

Bloom's Taxonomy 1956 |

Anderson and Krathwohl's Taxonomy 2000 |

|||

|

1. Knowledge: Remembering or retrieving previously learned material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

1. Remembering: Retrieving, recalling, or recognizing knowledge from memory. Remembering is when memory is used to produce definitions, facts, or lists, or recite or retrieve material. |

|||

|

2. Comprehension: The ability to grasp or construct meaning from material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

2. Understanding: Constructing meaning from different types of functions be they written or graphic messages activities like interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining. |

|||

|

3. Application: The ability to use learned material, or to implement material in new and concrete situations. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

3. Applying: Carrying out or using a procedure through executing, or implementing. Applying related and refers to situations where learned material is used through products like models, presentations, interviews or simulations.

|

|||

|

4. Analysis: The ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components so that its organizational structure may be better understood. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

4. Analyzing: Breaking material or concepts into parts, determining how the parts relate or interrelate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose. Mental actions included in this function are differentiating, organizing, and attributing, as well as being able to distinguish between the components or parts. When one is analyzing he/she can illustrate this mental function by creating spreadsheets, surveys, charts, or diagrams, or graphic representations. |

|||

|

5. Synthesis: The ability to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

5. Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing. Critiques, recommendations, and reports are some of the products that can be created to demonstrate the processes of evaluation. In the newer taxonomy evaluation comes before creating as it is often a necessary part of the precursory behavior before creating something. Remember this one has now changed places with the last one on the other side.

|

|||

|

6. Evaluation: The ability to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are:

|

6. Creating: Putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganizing elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing. Creating requires users to put parts together in a new way or synthesize parts into something new and different a new form or product. This process is the most difficult mental function in the new taxonomy. This one used to be #5 in Bloom's known as synthesis. |

Adapted from http://www.celt.iastate.edu/teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy/

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy

John Biggs developed a Cognitive taxonomy closely related to Bloom's/Anderson's taxonomy - the SOLO taxonomy. People generally tend to relate to either Biggs or to Bloom's/Anderson.

Adapted from http://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

The Miller model for assessing competence

The Miller Pyramid is an learning model which is particularly relevant to assessing learning oucomes of clinical competence. It was designed for use in health education, but can be applied to other fields of knoweldge too.

The Pyramid is based on progressive development across a range of abilities, measured according to a workplace context.

At the lower levels of the pyramid, the aim is for the students to understand the theory that is the foundation of clinical competence. They develop this understanding from knowledge transmission learning activities, such as lectures, readings, and demonstrations.

At the upper levels, the aim is for them to integrate the theory (intellectual skills), their psychomotor skills, and professional attitudes, to perform as health professionals in different contexts.

![Miller's pyramid [Source: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory] Miller's pyramid [Source: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916132/mod_book/chapter/105881/Miller%20v1.png)

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Writing course objectives

Learning objectives may be written with respect to knowledge, skills and attitudes.

For an objective to be claimed, it must be assessed; therefore, there must be an alignment between objectives and assessments.

Typically, it's easier to assess knowledge and skills than attitudes.

There are typically three parts to an objective:

1. The stem

A course objective starts with a stem, which would typically look something like this:

“On completion of this course students will be able to...”

.

2. The performance verb

Next, there is a performance verb, which should NOT be placed in the stem. For example:

“On completion of this course students will be able to explain...”

Typical performance verbs include:

- Identify..........

- Explain...........

- Apply.................

- Analyse..........................

- Critique......................

- Synthesise....................

Try to avoid verbs such as “understand” or “appreciate”: they are difficult to assess.

.

3. The object

Finally, you need to add the object to which the verb relates:

“On completion of this course students will be able to (STEM) explain (VERB) basic anatomical and physiological terminology, and describe the structure and organisation of the human body (OBJECT).

Some (not all) instructional documents about how to write learning objectives state that the objective should denote a standard to be achieved. This needs to be seen at two levels.

- The verb used is a performance standard. For example ‘apply’ denotes a performance standard. However, it doesn't suggest how the verb will be measured.

- At UniSA, the performance standard relating to measuring is usually articulated in accompanying documents such as the relevant assessment criteria / feedback proforma, and so it doesn't need to be stated in the objective. The accompanying criteria and feedback sheets need to align with the objective.

.

Assessing attitudes

Attitudinal objectives require a different set of verbs and are at times problematic. Examples of attitudinal verbs are:

- Cooperate

- Engage

- Respond

Other important things to consider

- What year level is the course? Lower level objectives might be appropriate in the early years of a program but probably not in the later years.

- What knowledge, skills and attitudes will your students come in with?

- What types of learning does your profession require?

- What courses and what learning will the students be doing simultaneously and subsequently?

- How will you assess the objective? You cannot claim an objective you have not assessed. It must be observable and measurable in some way.

- Higher level objectives tend to mean that deeper learning is more likely, but foundation learning may have to occur first.

- Skills, like problem solving and team work, have to be taught before they can be used.

| Ask us |

Tell us |

|

|

Assessing students

We assess student work so both teachers and learners can see what students know, so that teachers can know whether students have achieved the learning outcomes, and so that students know what they need to do in order to improve.

Both the selection of the assessment method and the design of the specific task are important. The quality of the questions we ask or the specific activities we design to assess students' learning is a key factor determining their ability to demonstrate and assess their learning towards the intended outcomes.

Note that assessment is integral to the everyday processes of learning and teaching throughout a course, rather than something that just happens at the end to measure student performance. In the same way, it is critical to start considering the assessment in the early planning of a course, so that the content is built around the learning outcomes and evidence of achievement of learning outcomes, rather than the assessment being built around the content, as often happens.

We have prepared a resource which presents some perspectives on assessment.

You can use this resource to underpin your course assessment strategies.

Just click on the particular title below to go to the relevant resource page:

Flipping and blending

The term Blended Learning can refer to the combining of any two approaches to learning. However, lately it has come to mean using both face to face and online approaches to teaching and learning. There are no rules that say how much face to face or how much online qualifies in order to be called blended.

![Flipped classroom [Source: http://facultyinnovate.utexas.edu/teaching/flipping-a-class]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916132/mod_book/chapter/109892/flippedflowmodel.png)

It could be said that in HSC every course (except those completely online with no face to face components) is a blended learning course. Blended does not mean interactive or student-centered; it just means that at least one part is face to face and at least one part is online.

Another point about educational definitions is that from time to time, an old approach to teaching and learning is resurrected, given a make-over and a new name: this is what has happened with the Flipped Classroom.

There is nothing new about a flipped classroom - it refers to those teaching events where students encounter new knowledge for the first time outside of the class and 'discuss' what the new knowledge means inside the class.

If you have ever set your students a reading to do outside of the class, and then discussed what that reading means inside the class, then you have flipped your classroom.

The following presentation may help you to understand and implement flipped learning in your classes.

| Ask us |

Tell us | Find us |

|

|

|

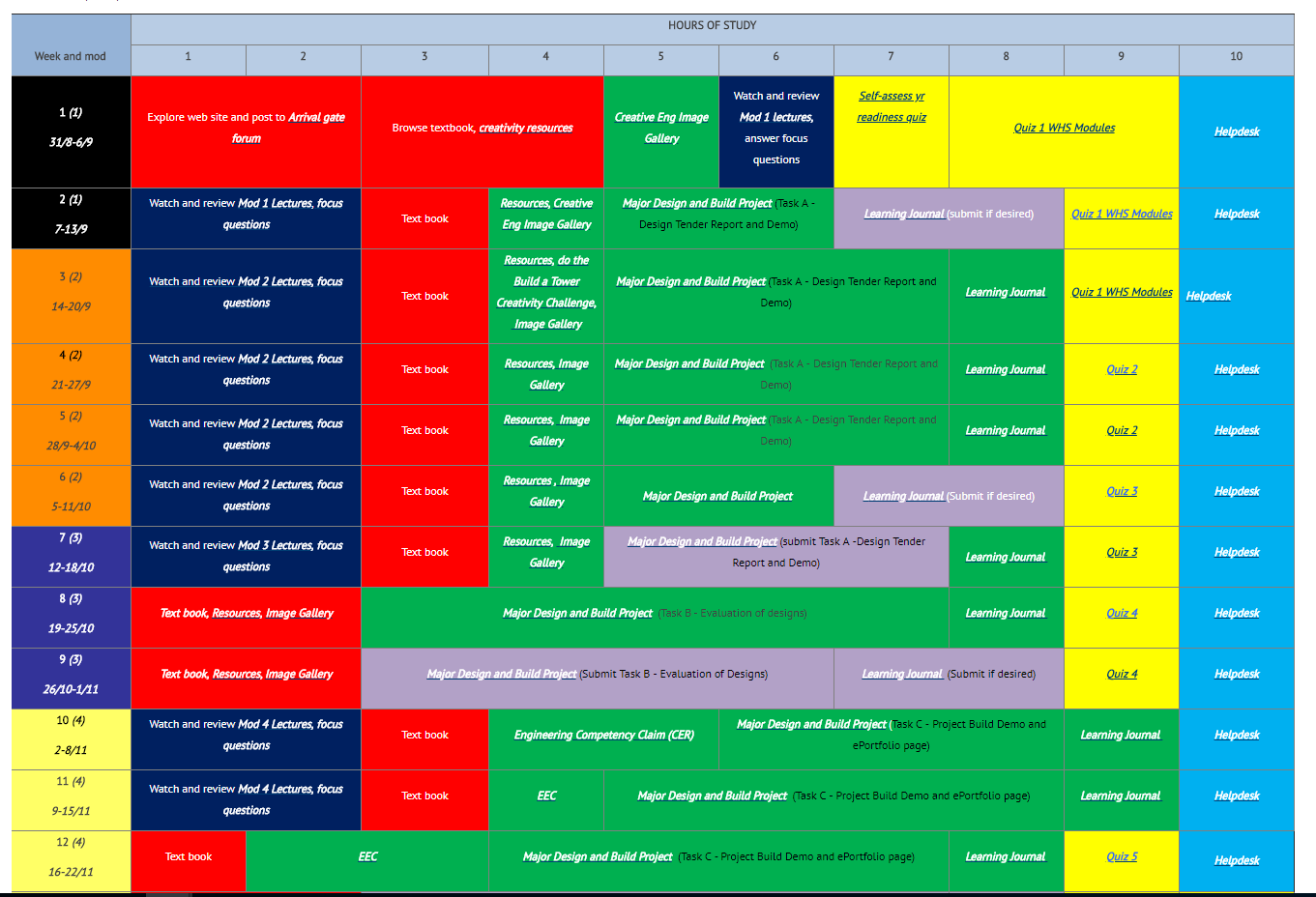

Course planners and study schedules

A detailed time budget or study schedule will let the students know exactly what is expected of them for each week of the course.

It should include times and timings for ALL course activities - attending or viewing lectures, attending tutorials, reading and noting readings, reading and contributing forums posts, studying for exams and tests, actually doing exams and tests, and working on other assignments. It should also include deadlines such as assessment submission dates.

If your planner is online, you can link each entry in the planner to the actual activity on the course website.

Preparing this type of detailed planner is actually a good exercise for you to undertake when you are planning and designing the course, because it gives you the opportunity to visually represent and observe the pattern of activities which you will expect your students to follow throughout the course.

Note that normally, you should not ask for students to devote more than 10 hours per week for all course activities (10 hours x 4 courses in a FTL adds up to a 40-hour per week study load).

You can see an example of part of a study schedule/guide below (these activities would all be linked on a course website). You can also see another example, using a Moodle book to lay out the tasks for each week.

Evaluating a course

Evaluation needs to be a formative process that influences student learning, not a merely an institutional process done at the end of a course 'to' both academics and students.

Evaluation is not only about students, but needs to consider all stakeholders.

|

Two big issues with the UniSA formal evaluation tool (MyCourseExperience) are the low response rates, and the problem of how to influence students' perception of the course and the teaching to obtain appropriate recognition.

We have an extended section on evaluation here.

In this section we look at inappropriate student comments and how to improve your evaluation outcomes in ethical ways.

Action research and continuous evaluation

This type of evaluation involves assessing a course as it is actually running, and reflecting continually on their own actions, with the aim of improving 'on the go', rather than waiting for the next iteration of the course.

John Hattie argued that for improvements to happen in the classroom, it is critical that teachers have the right mind frame to become effective evaluators of their own practice; in fact, effective continual evaluation is one of the few elements in a classroom which does lead to noticeable increase in student learning.

"Effective teachers change what is happening when learning is not occurring... An effective teacher makes calculated interventions, and provides students with multiple opportunities and alternatives to learn, at both surface and deep levels." (Hattie, J 2011, Visible learning for teachers.)

Ellie Chambers and Marshall Gregory have written on the process of 'action research' to evaluate courses and teaching, in their book Evaluating Teaching: Future Trends, in the book Teaching & Learning English Literature. They talk about the ways in which teachers can satisfy themselves about their courses and performance, quite separately from the formal evaluation processes the institution has put in place.

Action research means that teachers investigate and reflect on courses of action to improve various elements of their course and compare the aims and intentions to what actually happened on the ground, by continual monitoring of the student engagement and progress, by peer and student review, and by careful consideration of conflicting feedback.

.

Strategies to help with course evaluation

The following concertina presentation lists some ideas and

tips which may help you with evaluation. Just click on the three headings.

Useful links and references

UniSA course and teaching feedback

Other useful resources include:

Zabaleta, F 2007, 'The use and misuse of student evaluations of teaching', Teaching in Higher education, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 55–76.

Macdonald, R 2006, 'The use of evaluation to improve practice in learning and teaching', Innovations in Education and Teaching International, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 3–13.

Baldwin, C, Chandran, L, & Gusic, M 2011, 'Guidelines for Evaluating the Educational Performance of Medical School Faculty: Priming a National Conversation', Teaching and learning in medicine, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 285–97.