Assessing students

| Site: | learnonline |

| Course: | Teaching and learning in Health Sciences |

| Book: | Assessing students |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 21 January 2026, 9:44 AM |

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

Assessment for, of and as learning

When designing assessment, we really need to think about what we want students to learn, and what it is we need the assessment to do.

Assessment is fundamental to student learning, but it's not just about measuring that learning. Of course, measuring learning is important, but there can be other purposes to assessment.

In fact, not only should students learn from their assessment; assessment for learning should also inform our teaching.

The diagram below (adapted from NSW Education Standards Authority, Assessment for, as and of learning) illustrates three approaches to assessment:

- assessment for learning

- assessment of learning

- assessment as learning

Click on the circles to see more about each approach.

In a perfect course, learning and assessment would be indistinguishable: the learning would be supported by components from the assessment for, of and as learning, and the quality assurance or end accreditation would be dependent on the assessment of learning.

Assessment for learning

Assessment for learning is one element of assessment which is often neglected in teaching. It basically means that teachers use evidence about their students' knowledge, understanding, and skills to feed back into their teaching, and thus reshape their teaching approaches.

Formative assessment does this to a certain extent, but ideally, it should be formative from the point of view of both the teacher and the student.

You can see more about the principles of assessment for learning in the diagram below (adapted from the 'Assessment for learning: 10 principles' document, produced by the Assessment Reform Group in 2002).

Click on the information icons to see more detail about each principle.

Principles of assessment

Principle: Clarity

Assessment needs to support learning and measure the learning of an objective (even formative assessment). It is vital to have a clear purpose, and this purpose will form the basis of the marking rubric.

Principle: Accurate measurement

Assessment should measure performance against a fixed set of standards or criteria.

- Criterion-referenced assessment measures a student’s performance based on his/her mastery of a specific set of skills, or on the knowledge the student has (and doesn't have) at the time of assessment. The student’s performance is NOT compared to other students’ performance on the same assessment.

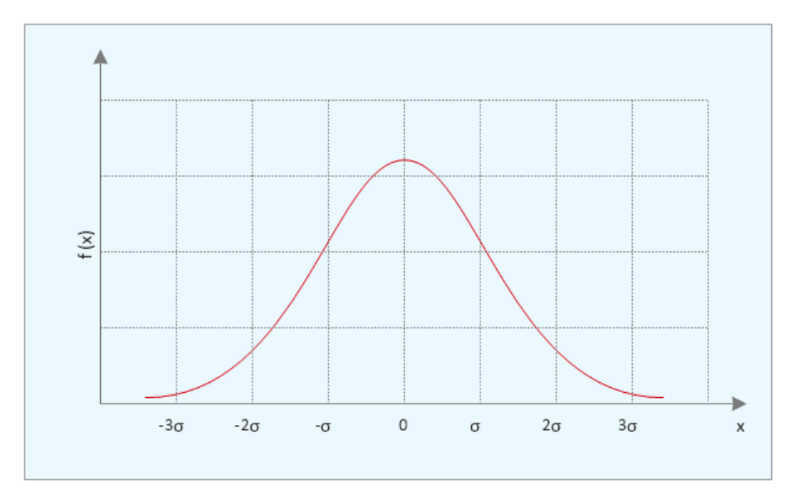

- Norm-referenced assessment, on the other hand, measures a student’s performance in comparison to the performance of the course or class cohort. Normative scoring is based on a bell curve. You can see an example in the diagram below: only half of the students can score above 50 percent, regardless of the quality of their submission.

Principle: Relevance and transferability

Modern university assessment is often based on a narrow range of tasks, with the emphasis on knowing rather than doing - this limits the range of skills which the students are asked to demonstrate.

Ideally, an assessment task should address the skills you want the students to develop, in the professional context in which they would be applied.

This gives the assessment a sense of 'real' purpose beyond just the abstract measuring of 13 weeks learning.

It also gives the assessment a 'real audience' over and above the marker.

Principle: Reliability

If an assessment is reliable, it is explicit in terms of the learning outcomes it is measuring and the criteria by which the student is being judged.

The assessment criteria should be sufficiently detailed to ensure uniformity of marking across multiple students, cohorts and markers.

In fact, if the criteria and marking schemes for a particular assessment are totally reliable, any number of independent markers can be given a single student's submission, and they should allocate exactly the same mark (and feedback).

Principle: Validity

A key question for assessment is ... does it measure what we want it to measure? This is the principle of validity, which requires that there be a genuine relationship between the task and the learning required to complete the task.

A valid assessment will assess the student's abilities in the exact learning outcome for which it is designed, and nothing else. For example, if an assessment asks a student to analyse, it should test whether the students can actually analyse material, not whether they can:

- describe how to analyse

- recite a rote description of an analysis

- compare other analyses

- and so on

Principle: Transparency

A transparent assessment

means that every stakeholder has access to clear, accurate, consistent and

timely information on the assessment tasks and procedures, and there are no

'hidden agendas' within the assessment.

Prior to the assessment, students and staff should know the purpose, task and marking criteria for the assessment.

After the assessment, marking processes and feedback should be visible to the relevant student.

This principle is closely aligned to the principle of reliability, and so is also an important aspect of rubric development.

Fit for purpose

In this video, Prof Sally Brown discusses the concept of 'fit-for-purpose' assessment, arguing that assessment should:

- be built in, not bolted on

- authentically assess the learning outcomes

- stimulate learning

When developing fit-for-purpose assessment, the five key questions are:

- Why are we assessing?

- What is it we are actually assessing?

- How are we assessing?

- Who is best placed to assess?

- When should we assess?

You can see a presentation from Sally which delves further into these question.

.

Interesting resource

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

Programmatic models of assessment

There are a variety of models for thinking about assessment: for example, most people know of the Bloom's Taxonomy, and the Miller Model is commonly used to assess clinical learning outcomes.

In this section, we look at some of the programmatic models frequently used in higher education.

..

Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning Domains

Most models have their conceptual roots in 'Bloom's Cognitive' taxonomy.

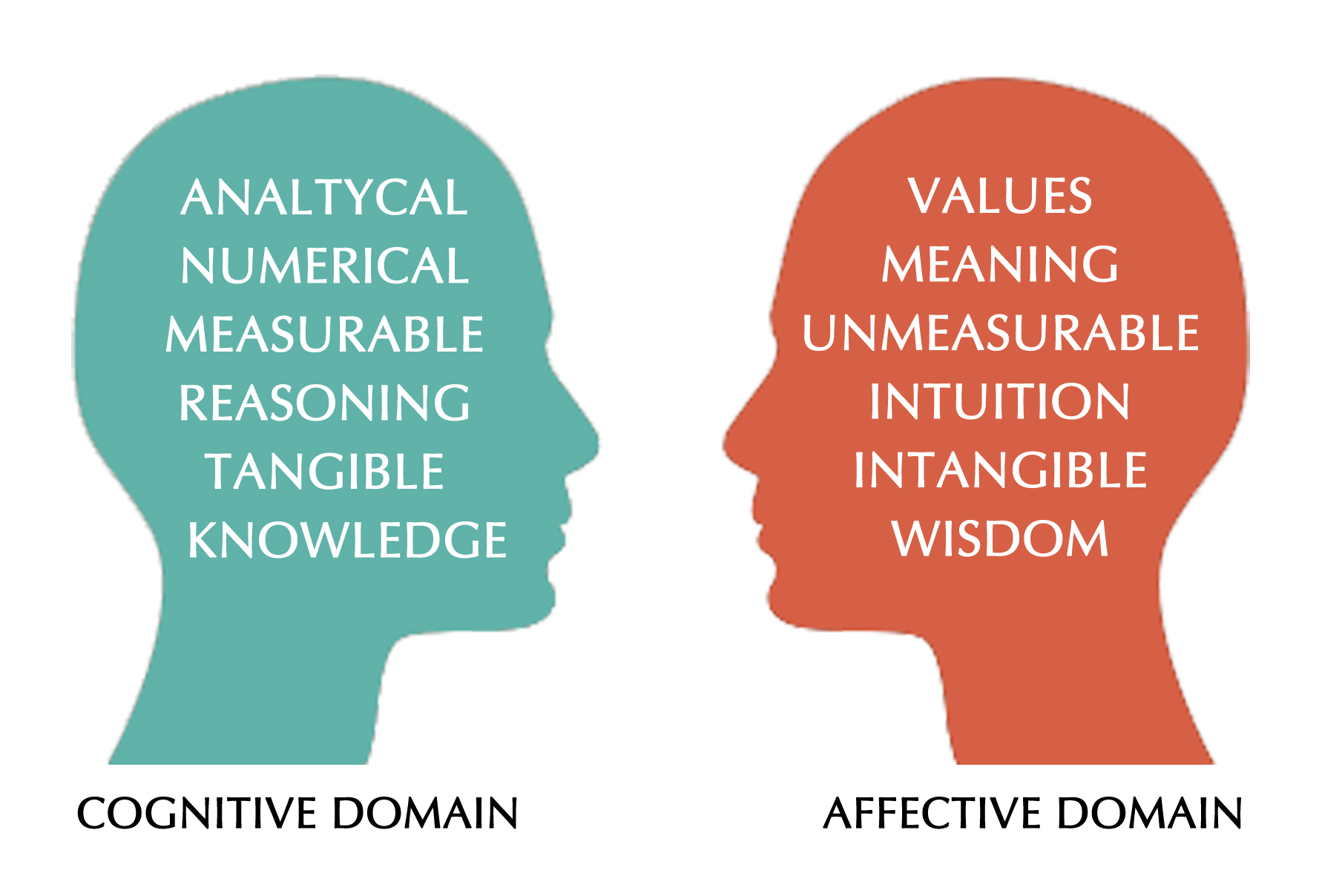

The collaboration that created Bloom's Cognitive taxonomy also created two other taxonomies: the 'Affective Domain' taxonomy and the 'Psycho-motor Domain' taxonomy.

- The cognitive domain is about thinking / conceptualisation (see Anderson's taxonomy below).

- The affective domain deals with ethics, values and behaviours, which are very hard to measure.

- The Psycho-motor domain deals with physical education: motor / muscular skills and things like expressive movement such as dance.

.

Bloom's cognitive domain (Bloom's Taxonomy 1956)

- Knowledge: Remembering or retrieving previously learned material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: know, identify, relate, list, record, name, recognize, acquire

- Comprehension: The ability to grasp or construct meaning from material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: restate, locate, report, recognize, explain, express, illustrate, interpret, draw, represent, differentiate

- Application: The ability to use learned material, or to implement material in new and concrete situations. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: apply, relate, develop, translate, use, operate, practice, calculate, show, exhibit, dramatize

- Analysis: The ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components so that its organizational structure may be better understood. Examples of verbs that relate to this function re: analyze, compare, probe, inquire, examine, contrast, categorize, experiment, scrutinize, discover, inspect, dissect, discriminate, separate

- Synthesis: The ability to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: compose, produce, design, assemble, create, prepare, predict, modify, tell, propose, develop, arrange, construct, organize, originate, derive, write, propose

- Evaluation: The ability to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: judge, assess, compare, evaluate, conclude, measure, deduce, validate, consider, appraise, value, criticize, infer

Adapted from http://www.celt.iastate.edu/teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy/

.

Bloom's affective domain

|

Category or 'level' |

Behavior descriptions |

Examples of experience, or demonstration and evidence to be measured |

'Key words' (verbs which describe the activity to be trained or measured at each level) |

|

1. Receiving |

Open to experience, willing to hear |

Listen to teacher or trainer, take interest in session or learning experience, take notes, turn up, make time for learning experience, participate passively |

Ask, listen, focus, attend, take part, discuss, acknowledge, hear, be open to, retain, follow, concentrate, read, do, feel |

|

2. Responding |

React and participate actively |

Participate actively in group discussion, active participation in activity, interest in outcomes, enthusiasm for action, question and probe ideas, suggest interpretation |

React, respond, seek clarification, interpret, clarify, provide other references and examples, contribute, question, present, cite, become animated or excited, help team, write, perform |

|

3. Valuing |

Attach values and express personal opinions |

Decide worth and relevance of ideas, experiences; accept or commit to particular stance or action |

Argue, challenge, debate, refute, confront, justify, persuade, criticize, |

|

4. Organizing or Conceptualizing Values |

Reconcile internal conflicts; develop value system |

Qualify and quantify personal views, state personal position and reasons, state beliefs |

Build, develop, formulate, defend, modify, relate, prioritize, reconcile, contrast, arrange, compare |

|

5. Internalizing or Characterizing Values |

Adopt belief system and philosophy |

Self-reliant; behave consistently with personal value set |

Act, display, influence |

Adapted from http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/affective/index.html

.

The psychomotor domain

Bloom never completed the Psychomotor Domain. The most recognised version was developed by Ravindra H. Dave.

|

Category or 'level' |

Behavior Descriptions |

Examples of activity or demonstration and evidence to be measured |

'Key words' (verbs which describe the activity to be trained or measured at each level) |

|

Imitation |

Copy action of another; observe and replicate |

Watch teacher or trainer and repeat action, process or activity |

Copy, follow, replicate, repeat, adhere, attempt, reproduce, organize, sketch, duplicate |

|

Manipulation |

Reproduce activity from instruction or memory |

Carry out task from written or verbal instruction |

Re-create, build, perform, execute, implement, acquire, conduct, operate |

|

Precision |

Execute skill reliably, independent of help, activity is quick, smooth, and accurate |

Perform a task or activity with expertise and to high quality without assistance or instruction; able to demonstrate an activity to other learners |

Demonstrate, complete, show, perfect, calibrate, control, achieve, accomplish, master, refine |

|

Articulation |

Adapt and integrate expertise to satisfy a new context or task |

Relate and combine associated activities to develop methods to meet varying, novel requirements |

Solve, adapt, combine, coordinate, revise, integrate, adapt, develop, formulate, modify, master |

|

Naturalization |

Instinctive, effortless, unconscious mastery of activity and related skills at strategic level |

Define aim, approach and strategy for use of activities to meet strategic need |

Construct, compose, create, design, specify, manage, invent, project-manage, originate |

Adapted from http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/psychomotor_domain.html

.

Bigg's Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy

John Biggs developed a Cognitive taxonomy closely related to Bloom's/Anderson's taxonomy - the SOLO taxonomy. People tend to relate to one or the other of these.

Adapted from http://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/

.

The Miller model for assessing competence

The Miller Pyramid is very relevant to learning outcomes in clinical competence. In this model, the student developed progressively from gathering knowledge, to being able to interpret and apply that knowledge, to being able to demonstrate knowledge in performance, to - at the highest level - performing in a workplace context.

At the lower levels of the pyramid, the aim is for the students to understand the theory that is the foundation of clinical competence. They develop this understanding from knowledge transmission learning activities, such as lectures, readings, and demonstrations.

At the upper levels, the aim is for them to integrate the theory (intellectual skills), their psychomotor skills, and professional attitudes, to perform as health professionals in different contexts.

![Miller's pyramid [Source: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory] Miller's pyramid [Source: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/e-learning/setting-learning-objectives/some-theory]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916694/mod_book/chapter/103501/Miller%20v1.png)

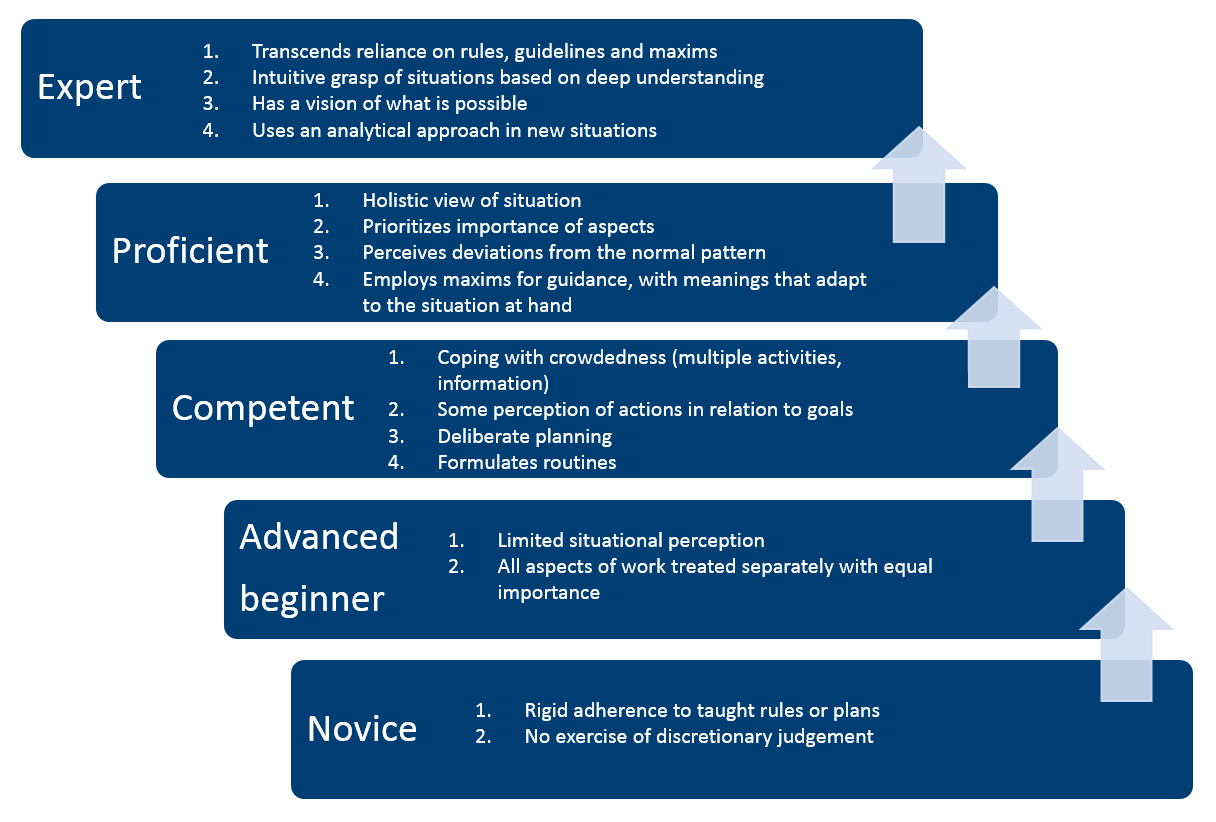

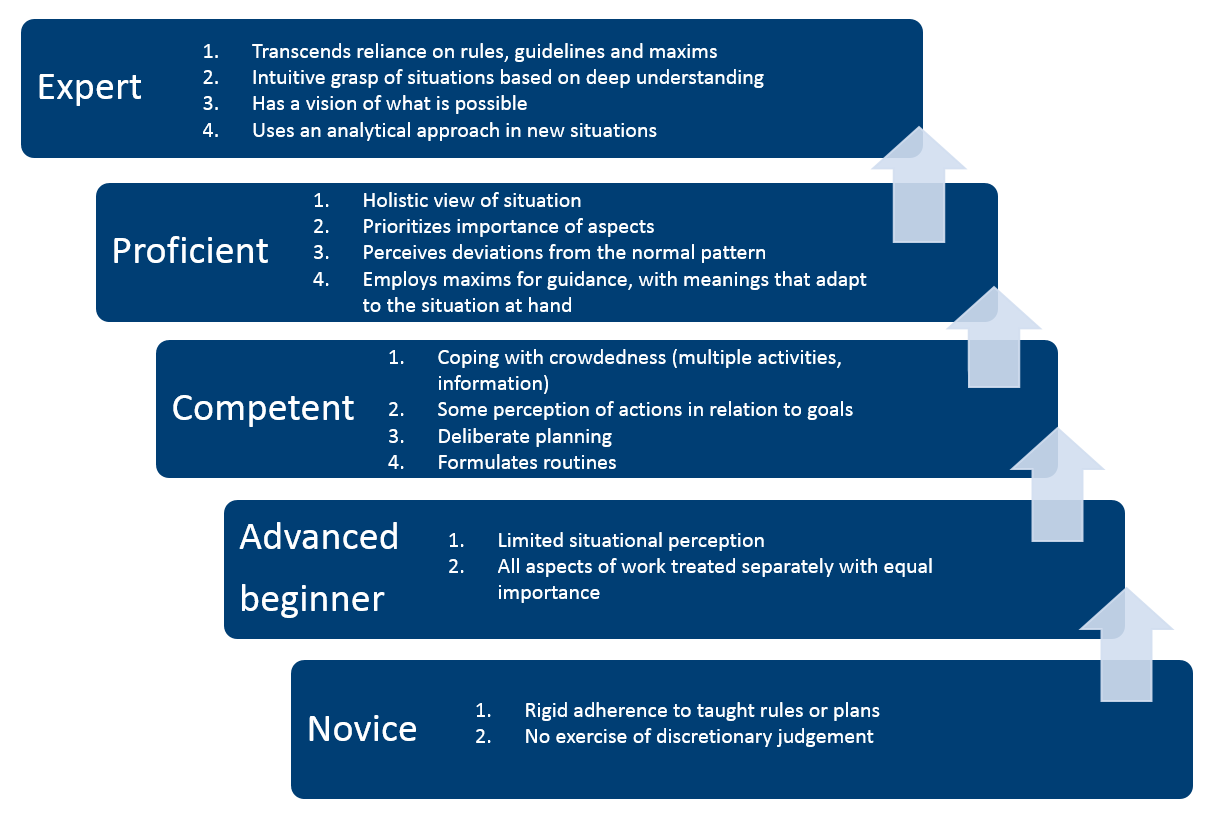

The Dreyfus model of skill acquisition

The Dreyfus model of skills acquisition is based on approaches which work on instruction and experience. In this model, the student passes through five stages:

- novice

- competence

- proficiency

- expertise

- mastery

A skilled student depends more on experience than on principles, and has a fresh view of the task environment in a different way.

Dreyfus, SE & Dreyfus, HL 1980, A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skills acquisition

.

Interesting resource

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

Why are rubrics so important?

Rubrics are marking tools which are developed hand-in-hand with assessment tasks; they reflect the intention and purpose of the assessment, and, through the assessment, the learning outcomes of the course. They aim to separate out the standards of student work, and communicate those standards to students and other staff - that is, they bring clarity and transparency to the assessment.

In teaching and learning, rubrics are far more important and powerful tools than generally assumed.

It could be argued that the development of the rubric is more important than the development of the detailed assessment task, because the rubric is critical in ascertaining whether or not the students have achieved the learning outcomes of the course. At its worst, a poor rubric can result in students passing the assessment, and even the course, even though they haven't achieved the outcome that you are looking for.

Rubrics communicate to students (and to other markers) your expectations in the assessment, and what you consider important. The rubric tells students much about the assessment, so you need to make sure that it's telling them what you want them to hear. You should be able to give a well-written rubric to students INSTEAD of the assessment, and they should be able to identify what the assessment is and what is important - in fact, in some cases, it may be possible for the students to negotiate the assessment task with you, based on the rubric.

You can also use good rubrics as teaching resources, to give students a clear indication of any critical gaps or weaknesses in their performance, what they need to do to improve, and where to focus their efforts (feed-forward rather than feedback).

Good rubrics can also go a long way in eliminating awkward conversations on questions such as, 'Why did I get this mark', 'This mark is not fair', etc.

In order to create a really powerful rubric, there are some important steps to consider, which we have outlined below.

However, one other point before you start - try not to start out by using a template. There are literally hundreds of them out there - some good, some terrible - but it is important that your rubric is absolutely aligned to your course outcomes and your assessment outcomes, and using a provided template can skew the process. You need to consider the unique aspects of your assessment and outcomes independently of pre-formatted templates. If you definitely want to use a template, first work through the rubric development process, and then find a template which fits your requirements.

.

The steps ...

1. Stand back. The first step must ALWAYS be to take a good, hard, holistic look at the very foundation of your assessment task - what is the purpose of this assessment?

Always, always, always start by considering the Big Idea of the assessment. What is the one main essential purpose of this assessment - what it is that students MUST do to pass? What learning objectives do you intend the assessment to further or to demonstrate?

Ideally, there should only be one Big Idea for every assessment (which might focus on more than one course objective). Take all the time that you need to think about this, because if it is not reflected as the basis of your rubric, the rubric is not only not effective as a marking tool, but could actually be causing harm.

.

2. Next ... where does your assessment fit with the program and with the course?

Your assessment must fit with the program objectives and with the course objectives. If it doesn't, you may need to change the assessment, or even consider changing the course objectives. It may be that the Big Idea for your assessment is actually a re-statement of one of the course objectives ... nothing wrong with that. You need to consider the program dimension to make sure that the assessment and rubric reflect the appropriate stage in the student's progress.

As the assessment aligns to the program and course, so too should the rubric. If the assessment is aimed at demonstrating achievement of higher order, more complex learning outcomes such as critical thinking and analysis, the rubric must be able to quantify that.

.

3. The big question ... holistic or analytical?

A holistic rubric judges an assessment product as a whole, without judging the various component of the assessment separately. An analytic rubric judges separate elements, components or aspects of the assessment product..

There are strengths and weaknesses with both types of rubric, depending on your situation. For example, a holistic rubric is more valuable in judging whether or not students have achieved the Big Idea - but requires extensive discussion to ensure that multiple markers are all on the same page.

Holistic rubrics are often useful at the more complex levels of learning, especially in creative or hard-to-quantify disciplines. They are also useful for judging achievement in the affective domain - for example, valuing, responding, or being receptive to ideas or material.

Our advice is that if the assessment 'whole' is bigger than the parts, then use a holistic rubric (an essay is a good example of this). If each of the components or aspects are all important, then use an analytical rubric.

However, in developing an analytical rubric, be careful not to over-simplify or over-segregate the assessment elements or components, because this can lead to trivialising and loss of the Big Idea. A fine example of this is dividing up an essay or report task based on the various sections of the document - introduction, body, conclusion, language use, referencing, etc. You may end up with a rubric which comfortably passes students who have no real idea of the Big Idea, and have not actually solved the problem posed in the assessment.

4. The line in the sand ... what is a pass?

The most critical element of the rubric, and the one on which you should spend the most thought, is what we call the Minimum Acceptable Level of Performance. The whole purpose of this is to accurately separate out competent students from incompetent students – the passes from the fails. The rubric MUST be set up so that no student can pass without achieving this minimum level in the critical assessment outcomes, especially higher order and hidden outcomes.

To find this, think about what is the minimum point at which you would be happy with a student's performance in the Big Idea, taking into considering the complexity of the task, the student level and experience, and the outcomes which you are assessing.

Have a very clear picture in your head of what the Minimum Acceptable Level of Performance looks like, for students at this level, in this type of activity, according to these course objectives. This minimum level of performance will become your 'P1 pass point': the defining point for the student to pass the assessment. Receiving a P1 for an assessment should indicate to both student and teaching staff that the student has achieved an acceptable professional level of performance in these assessment outcomes relative to their time in the program. Higher levels of performance will be encouraged and rewarded, but are not essential for professional effectiveness.

You can see an animation of different Minimum Acceptable Levels of Performance (MALOPs) below - just move the arrow on the slider backwards and forwards.

.

5. Good, better, best ... bad. How do you establish other levels of performance?

Using the minimum level of performance as a pivot, decide on the other levels of performance, especially the levels of pass. You can do this by establishing in your mind what you think would classify as an outstanding student response to the task, completely fulfilling all of the assessment outcomes – this becomes your HD. You can then work up from a pass to a HD, deciding on your levels of performance.

Forming a picture of a failure is much harder, because it's virtually impossible to anticipate all the possible ways in which students might not achieve the assessment outcome. You may need to keep this section of the rubric quite general, but make up for this by providing very specific, detailed feedback to the failing students. Some teachers populate the fail sections of the rubric by outlining the 'typical critical errors' which commonly prevent students from achieving the Big Idea.

If you have chosen to develop an analytical rubric, you can now draw out performance criteria which encompass the various assessed aspects of the task. Only create as many as you need to accurately assess the student. You should give each performance criteria a weighting which will the assessment outcomes – again, adjust the weightings to make sure that a student can’t pass without having achieved the critical outcome (even if they did brilliantly in all the other outcomes!).

Finally, before you present the rubric to your students and staff, give it the acid test ... go back and test it to see whether it is possible for a student to pass without achieving the Big Idea.

.

6. Getting everyone on board. Discuss the rubric with students and staff.

We can't emphasise enough how important it is to discuss the rubric in detail with students and with other marking staff, to the point that everyone is absolutely on the same page in their understanding of the language it uses, the Big Ideas it is judging, and the guidance it gives. Remember that different words and terms can mean totally different things to different people. You might understand exactly what the rubric means to you, but others may have a quite different picture in their heads.

Take the time to compare and contrast the various levels of achievement and create a shared understanding. This may take quite a lot of time in discussion and negotiation, but if everybody is crystal clear on what the various levels of performance are, it will pay off in the long run.

.

Rubric scales

The scale will define the various levels of achievement above and below the minimum acceptable level. The most common scale for tertiary assessments is based on grades (distinction through to F2). However, other scales might be useful if you are setting a formative activity, or if your assessment is not suited to the full range of grades. Some options are:

- pass/fail

- qualitative descriptions (Excellent, Very good, Good, Satisfactory, Poor, Very poor)

- marks (either discrete or accumulative)

- percentages

Getting students to participate in writing rubrics and marking using rubrics

At the very least, your assessment rubric should be handed out to students prior to the assessment task, to make them aware of all your expectations related to the assessment task, and to help them to evaluate their own progression and readiness.

However, you can take your use of rubrics to another level by involving the students in their creation. This is a very powerful way to help them to build their understanding of what what different levels of understanding actually look like, and what differences there are between powerful and weak work.

Discussions of which performance criteria they think are important, and what the different performance levels actually mean increases the students' engagement in the assessment process.

Another effective strategy is to get the students to use your assessment rubric prior to the formal assessment, as a self-assessment exercise, or to get students to mark each other using the rubric. In this way, they become more cognisant of assessment processes and procedures, and improve their capacity to assess their own work.

Interesting links and resources

Biggs, J & Tang, C 2007, Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 3rd edn, McGraw Hill, Maidenhead.

David Birbeck's PowerPoint presentation on designing rubrics

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

An expert's view on assessment and feedback

Professor David Boud is Professor and Foundation Director of the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning, Deakin University, Melbourne and Research Professor in the Institute for Work-Based Learning, Middlesex University.

He is Emeritus Professor at the University of Technology Sydney and a Senior Fellow of the Australian Learning and Teaching Council (National Teaching Fellow).

.

The practice of practice-based assessment

This video is of a presentation by David on the dilemmas and tensions of practice-based assessment.

.

Interesting links

Assessment futures: This site provides information on:

- ideas and strategies to browse and consider, but no prescriptions for what you should do.

- ideas that are potentially applicable across a wide range of disciplinary areas.

- examples of how these ideas and strategies have already been used and tested.

- how to adapt and extend these ideas to suit your own subject matter and local circumstances." accessed 8 October 2013

Assessment 2020: Seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education.

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

The Dreyfus model of skill acquisition

The Dreyfus model of skills acquisition is

based on skill development through instruction and experience. In this

model, the student works through five developmental stages:

- novice

- competence

- proficiency

- expertise

- mastery

A student with greater skill depends less on theory and principles, and more on their experience. They also look differently at the environment in which they are working. The diagram below is adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dreyfus_model_of_skill_acquisition

.

Interesting resources

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

The principles of feedback

- Prioritise your ideas and understand their value. Limit your feedback to the most important issues. Consider the potential value of the feedback to the student. Consider how you yourself would respond to such feedback (would you be able to act on it?). Remember also that receiving too much feedback at one time can be overwhelming for the student.

- Concentrate on the work, not the student. Remember that you're discussing the work, not the student - try to keep all of your feedback centred on the academic aspects of the assessment, and how it relates to the course outcomes.

- Balance the content. Use the “sandwich approach”. Begin by providing comments on specific strengths, to give reinforcement and identify things the recipient should keep doing. Then identify specific areas for improvement and ways to make changes. Conclude with a positive comment. This model helps to bolster the student's confidence and keeps weaker areas in perspective. Example: “Your presentation was great. You made good eye contact and were well prepared. You were a little hard to hear at the back of the room, but with some practice you can overcome this. Keep up the good work!” Instead of:“You didn’t speak loudly enough, but otherwise the presentation went well."

- Be specific. Avoid general comments that may be of limited use to the student. Try to include examples to illustrate your statements. Remember, too, that offering alternatives rather than just giving advice allows the student to decide what to do with your feedback.

- Be realistic. Feedback should focus on what can be changed. It's frustrating for students to get comments on things over which they have no control. Also, remember to avoid using the words always and never.

- Be timely. Find an appropriate time to communicate your feedback. Being prompt is key because feedback loses its impact if it's delayed too long. Also, if your feedback is primarily negative, take time to prepare what you will say or write.

- Offer continuing support. Feedback should be a continuous process, not a one-time event. After offering feedback, make a conscious effort to follow up. Let students know you're available if they have questions and, if appropriate, ask for another opportunity to provide more feedback in the future.

Some sentence starters for sensitive feedback

There are two key things to consider here.

Firstly, think about where and when you are going to provide the 'sensitive' feedback.

Secondly, be careful of your non-verbal language and use 'I' statements. Some good examples appear below.

- I’m noticing that….

- It appeared as though….

- I was wondering why….

- I observed that some students seemed uncomfortable with ….

- The/Some students appeared to be …… (confused, uncertain, distracted etc.)

- Feedback based on personal experience

- I have found that ….

- Perhaps you could consider trying ……

- In my class I’m thinking of trying ……

- I think that situation was really tricky because …..

- I have experience a similar situation …. (empathic response)

Taken from RMIT's 'Giving feedback'.

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

What is moderation?

Consider this quote from a student course evaluation:

"….when we went and approach the lecturer about the assignment, she said, ‘You’ve got that freedom to do what you want’,

but she doesn’t have a plan of what she wants in the course booklet, so you’re not quite sure what she wants.

So you do what you think she wants, take into account what she said in class, but then she says, ‘That’s not really what I wanted’ ... you can’t win!"

There is no doubt that marking - or any kind of judging - can be very subjective, and can even depend on the mood of the marker.

This brings challenges to course coordinators in trying to make sure that students' work is marked in the way what they would like, so that the students' 'destiny' will depend on how somebody feels on the day (Flint, N & Johnson, B 2011, Towards Fairer University Assessment: Recognising the concerns of students, Routledge, Oxon).

Although people will have different ideas about what moderation means, the ALTC research indicates that most understanding of the term focuses on:

- Consistency in assessment and marking

- Processes for ensuring comparability

- Measures of quality control

- Processes to look for equivalence

- Maintainance of academic standards to ensure fairness

- Quality assurance

Marking and reviewing grades, in isolation, do not result in effective moderation. There are a series of processes and activities which contribute to moderation, including the design and development of the assessment, the running and marking of the students' work, and then the review process after the assessment has been completed.

The aim of moderation is to ensure that assessment is fair, valid and reliable. Moderation is especially necessary when assessment involves large units or multiple markers, occurs on different campuses, is subjective or differs across students.

UniSA and Divisional policy on moderation

The Assessment

Policies and Procedures Manual (APPM) is a comprehensive guide

to University policy and procedure on assessment principles and requirements.

The APPM states that: "Each division will ensure that moderation practices in its schools and courses are documented and consistent with the view of moderation outlined in 3.1.1 and 3.1.2.

.

Questions to ask when ensuring good moderation

The ALTC Moderation Toolkit is a comprehensive resource which outlines a series of key elements of effective moderation. We have summarised some of the elements below here in this interactive activity (if you are reading this on a phone or tablet, click here to see the interactive activity in proportion).

![]() Download this

information (20 KB)

Download this

information (20 KB)

Interesting resources

| .Ask us. | .Tell us . |

Writing multiple choice questions

Multiple choice questions can be an effective and efficient way to assess your students' learning, especially at the lower cognitive levels of recall and application, and even analysis and evaluation. They can be consistent and reliable methods of assessment for certain learning outcomes, and are relatively easy and fast to mark, more so if they are online.

However, if multiple choice questions are to be effective, they need to be carefully considered and planned. Writing multiple choice questions is not an easy task. There are several principles which you need to consider before even deciding on this form of assessment.

![Blooms revised taxonomy [Source: http://digitallearningworld.com/blooms-digital-taxonomy]](https://lo.unisa.edu.au/pluginfile.php/916694/mod_book/chapter/102509/Blooms.png)

.

The principles

1. Are Multiple Choice questions a suitable assessment for the course learning outcomes?

Firstly, you need to ensure that the questions you intend to ask provide rigorous evidence related to the achievement of the learning outcomes. There are limits to what can be tested using multiple choice questions.

For example, choosing from a limited set of potential answers is not an effective way to test skills of organisation, reflection, communicative abilities or creativity.

However, you can use MC questions to get students to interpret facts, evaluate situations, explain cause and effect, make inferences, and predict results. A MC problem that requires application of course principles, analysis, or evaluation of alternatives can be designed to tests students’ ability in higher level thinking. Furthermore, MC questions can be designed to incorporate multi-logical thinking, applying more than one facet of knowledge to solve the problem.

Start by thinking about competence. What would a student need to demonstrate or to convince you that they were competent in relation to the course objective that relates to the MCQ test / exam?

If your concept of competence cannot be met by a MCQ test / exam, you may need a different form of assessment.

Firstly, you need to ensure that the questions you intend to ask provide rigorous evidence related to the achievement of the learning outcomes. There are limits to what can be tested using multiple choice questions..

2. Are my MC questions effectively testing the learning?

To produce questions which are effective in assessment the students' understanding, you need to spend some time working on both the stem (the initial problem) and the alternatives (the list of suggested solutions).

In the alternatives, you will have a right answer and a number of distractors (wrong answers). It is critical that while there is only one right answer, the distractors are plausible options, but are also unambiguously wrong. In fact, if possible, the distractors should be designed to increase the learning for those students who get them wrong.

For example, when designing the distractors for a formative MC activity, consider the common errors that students make in the type of content you are testing, and design the distractors to follow those errors. Then you can incorporate feedback which corrects the students and shows them how to avoid these common errors. Which brings us to the final principle ...

.

.3. How can I incorporate useful feedback?

Properly designed and crafted feedback for online formative MC questions can be one of the more powerful tools in the online toolbox. If the distractors are carefully composed, and the feedback is contextualised for each distractor, you can produce a resource which is along the line of a tutorial, and has as much value.

The trick is to use the distractors to present solutions which may incorporate common errors, and then compose contextualised feedback which is quite specific to that error, shows students how to avoid it, and if possible, has links to further resources covering that content.

The feedback in online MC questions is an invaluable teaching tool, because the students are particularly receptive to this information when they are trying to improve assessment results, and eager to see where they have gone wrong in a testing activity.

.

Other considerations

In order to optimise the reliability of the MC test, you can focus a number of MC questions on a single learning objective.

Frame questions in a real-life context if possible, so that students are recalling and applying principles, rather than just recalling.

.

Technical dos and don'ts

There are a number of hints and tips for improving your multiple choice questions, which are given in the following online presentation.

Stream the presentation (about 9 minutes)

Download the presentation for playing offline (7.9 MB; unzip the zip folder, extract all files and play the index.html file)

You can also download a pdf version of these hints and tips (504 KB)

.

Interesting resources and links

Toledo, CA 2006, 'Does your dog bite?: Creating good questions for online discussions', International Journal of teaching and Learning in Higher Education, vol. 18, no. 2, pp.150–154.

Vanderbilt University Writing good multiple choice questions.

Morrison, S & Free, K 2001, 'Writing multiple-choice test items that promote and measure critical thinking', Journal of Nursing Education, vol. 40, pp. 17-24.

Collins, J 2006, Writing Multiple Choice Questions for Continuing Medical Education Activities and Self-Assessment Modules.